Difference between revisions of "Creeperopolis"

m (Text replacement - "Matzio" to "Xipilli") |

|||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

In 220 BC, after what is believed to have been a 30-year period of warring between various tribes following the fall of the proto-Creeperian civilization, seven tribes—the [[Amacha Tribe|Amacha]], the [[Chihueta Tribe|Chihueta]], the [[Iloqutzi Tribe|Iloqutzi]], the [[Imnoqueti Tribe|Imnoqueti]], the [[Llohechue Tribe|Llohechue]], the [[Tzachu Tribe|Tzachu]], and the [[Xuhuetí Tribe|Xuhuetí]]—formed a loose military alliance between themselves and established a de facto political entity among themselves called the ''Cuēpieopoxūeta'' ("Land of the Creeperans"), referred to by modern historians as the [[Creeperian Confederation]]. Its capital city was selected to be [[Xichútepa]] (not related to [[Old Xichútepa]], the capital city of the Kingdom of Xichútepa), which was also the capital city of the Chihueta. Although each tribe was lead by a ''tlatoani'', the confederation was collectively led by a leader known as the ''tlen se tlatoani'' ("first one who rules"), and the first ''tlen se tlatoani'' chosen by the confederation was [[Machtitín I of Creeperopolis|Machtitín I]] of the Chihueta. | In 220 BC, after what is believed to have been a 30-year period of warring between various tribes following the fall of the proto-Creeperian civilization, seven tribes—the [[Amacha Tribe|Amacha]], the [[Chihueta Tribe|Chihueta]], the [[Iloqutzi Tribe|Iloqutzi]], the [[Imnoqueti Tribe|Imnoqueti]], the [[Llohechue Tribe|Llohechue]], the [[Tzachu Tribe|Tzachu]], and the [[Xuhuetí Tribe|Xuhuetí]]—formed a loose military alliance between themselves and established a de facto political entity among themselves called the ''Cuēpieopoxūeta'' ("Land of the Creeperans"), referred to by modern historians as the [[Creeperian Confederation]]. Its capital city was selected to be [[Xichútepa]] (not related to [[Old Xichútepa]], the capital city of the Kingdom of Xichútepa), which was also the capital city of the Chihueta. Although each tribe was lead by a ''tlatoani'', the confederation was collectively led by a leader known as the ''tlen se tlatoani'' ("first one who rules"), and the first ''tlen se tlatoani'' chosen by the confederation was [[Machtitín I of Creeperopolis|Machtitín I]] of the Chihueta. | ||

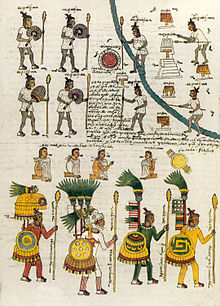

| − | From 200 BC to 145 BC, during the reigns of Machtitín I, [[Machtitín II of Creeperopolis|Machtitín II]], [[ | + | From 200 BC to 145 BC, during the reigns of Machtitín I, [[Machtitín II of Creeperopolis|Machtitín II]], [[Xipilli I of Creeperopolis|Xipilli I]], and [[Xiuhcoatl I of Creeperopolis|Xiuhcoatl I]], the Creeperans constructed the [[Great Pyramid of Xichútepa]], the largest pyramid in the world by volume and surface area. The pyramid served as the religious center of the confederation, and was the primary location where humans were sacrificed by Creeperian pagan priests to their gods. Additionally, beginning in 139 BC, the pyramid was also the location where the confederation's quasi-government distributed grain and food to Xichútepa's poorest residents, known as the ''[[Giving of the Maize|Imakaka in Sentli]]'' ("Giving of the Maize"). |

[[File:Gran Pirámide de Cholula, Puebla, México, 2013-10-12, DD 10.JPG|thumb|left|200px|alt=The ruins of a pyramid under a mountain which has a church build on top of it.|Ruins of the [[Great Pyramid of Xichútepa]] with the [[Church of Our Lady of Salvador]] built on top of it.]] | [[File:Gran Pirámide de Cholula, Puebla, México, 2013-10-12, DD 10.JPG|thumb|left|200px|alt=The ruins of a pyramid under a mountain which has a church build on top of it.|Ruins of the [[Great Pyramid of Xichútepa]] with the [[Church of Our Lady of Salvador]] built on top of it.]] | ||

Revision as of 02:23, 10 October 2023

Holy Traditionalist Empire of Creeperopolis Սանտո Իմպերիո Տրադիծիոնալիստա դե Ծրեեպերօպոլիս Santo Imperio Tradicionalista de Creeperópolis | |

|---|---|

Motto: Դեվաջո Դիոս յել Եմպերադոր Devajo Dios yel Emperador (Under God and the Emperor) | |

| Location | Sur and Ostlandet |

| Capital and largest city | San Salvador |

| Official language | Creeperian Spanish |

| Ethnic groups (2022) |

|

| Religion (2022) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary theocratic absolute monarchy and one party state under a de facto military dictatorship |

• Emperor | Alexander II (IC) |

| Augusto Cabañeras Gutiérrez (IC) | |

| José Sáenz Morales (IC) | |

| Legislature | General Courts |

| Council of Captain Generals | |

| Council of Viceroys | |

| Formation | |

| c. 2500 BC | |

| 220 BC | |

| 15 September 537 | |

• Emirate | 11 July 745 |

| 8 February 1231 | |

| 8 March 1565 | |

• Republic | 13 August 1729 |

| 7 September 1741 | |

| 4 July 1771 | |

| 31 December 1887 | |

| |

| 4 October 1949 | |

| 5 December 2022 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 3,188,570 sq mi (8,258,400 km2) (2nd) |

• Water (%) | 1.52 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2020 census | |

• Density | 166.99/sq mi (64.5/km2) (4th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium · 17th |

| HDI (2022) | high · 23rd |

| Currency | Creeperian colón (₡) (CCL) |

| Time zone | AMT–6, –5, –4, –3, –2, –1, +8 (Creeperian timezones) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy, AC/ADa |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +5 |

| ISO 3166 code | CR |

| Internet TLD | .cr and .ծր |

| |

Creeperopolis, officially the Holy Traditionalist Empire of Creeperopolis,[note 1] is a transcontinental country primarily located in Sur with parts of its territory in Ostlandet and Tierrasur. Mainland Creeperopolis—located in Sur—is bordered to the north by Montcrabe; to the south by Sequoyah and the Senvarian Sea; to the west by the Sea of Castilliano, Salisford, and El Salvador; and to the east by the Bay of Salvador and the Southern Ocean. Additionally, Creeperopolis controls the San Carlos Islands, 1,075 miles southwest of mainland Ostlandet, claims territory on the continent of Tierrasur, and completely enclaves the client state and religious country of the State of the Church. With an area of 3,188,570 sq mi (8,258,400 km2) divided into 31 departments, Creeperopolis is the largest country in Sur and the second largest in the world, after Quebecshire. Creeperopolis' largest and capital city is San Salvador, located near the geographic center of the country along the southern coast of Lake San Salvador; other major urban areas include Adolfosburg, Salvador, San Romero, La'Libertad, Victoria, Chalatenango, La'Victoria, and Tuxtla Martínez. As of 2023, Creeperopolis has a population of 532 million, making it the most populous country in the world.

Humans arrived in modern-day Creeperopolis 28,000 years ago in the modern-day department of San Romero. Ancient Creeperian civilization began around 2500 BC as city-states were formed by the people living around the San Romero River. The first kingdom to emerge in the area was the Kingdom of Xichútepa which existed from 1650 BC to 1578 BC, while the strongest kingdom of the era was the Kingdom of Cuscatlán which existed from 1580 BC to 867 BC. The eruption of the Chicxulub volcano in 250 BC ended the proto-Creeperian civilization and allowed for the rise of the Creeperian Confederation in 220 BC. The confederation was transformed into a kingdom in 537 AD but it was conquered by the Caliphate of Deltino in 745. The Deltinians formed the Emirate of Rabadsun, a rump state of the Creeperian kingdom they conquered.

The Creeperans of Rabadsun rebelled and formed their own kingdom on 1231. Creeperopolis and Deltino were in near-constant warfare from 1231 until the fall of Deltino's capital in 1326. The kings of Creeperopolis held absolute power until 1565 when a constitutional monarchy was established with the formation of an elected parliamentary body. The country's prime minister held most of the country's power from 1565 until 1729 when the monarchy was abolished. The country experienced civil war from 1730 to 1741 between monarchists and republicans; the civil war ended with the restoration of the monarchy in 1741, although the monarchists claimed that the monarchy had never been abolished. In 1771, the parliament was abolished and an absolute monarchy was reestablished; in 1778, the country was declared to be an empire.

The country experienced a war of succession between 1783 and 1790 which resulted in a victory for Emperor Manuel IV; he was overthrown in 1833 and was replaced with Adolfo III, his great nephew. The absolute monarchy ended in 1887 when a new parliament was established and the position of prime minister was restored. The Second Parliamentary Era was marked by political violence and instability which culminated in the outbreak of the Creeperian Civil War in 1933: conservative and fascist parties supported Emperor Romero I while liberal and communist parties supported Emperor Miguel VII. The civil war witness numerous atrocities and war crimes, most infamously the De-Catholization, a genocide and ethnocide instigated by supporters of Miguel VII, the National Council for Peace and Order, which resulted in 9 to 11 million deaths. The faction which supported Romero I, the Catholic Imperial Restoration Council, won the civil war and purged and suppressed all left-wing ideology following the civil war. Following a 2003 military coup d'état, the Creeperian government has been ruled by the monarchy, the Creeperian Armed Forces (FAC), and the Creeperian Initiative (IRCCN y la'FPPU), the country's sole legal political party.

Creeperopolis is one of the most influential countries in the world. It has been involved in several foreign wars, often times as a result of direct military intervention to support its own interests. Creeperopolis is a founding member and de facto leader of the Cooperation and Development Coalition (CODECO), a global military and economic alliance. As a result of the country's large population and global influence, Creeperian Spanish is one of the most widely spoken languages in the world. Creeperopolis has the world's second largest economy, largely as a result of its large agriculture and aerospace industries, tourism, and exports. The country's currency is the colón.

Despite its wealth and power, Creeperopolis is one of the most corrupt and undemocratic countries in the world, being described as a totalitarian state. The country's government is openly hostile against democracy, liberalism, and freedom of speech. Human rights are consistently a topic of concern; the country is frequently accused of committing human rights abuses, crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, and war crimes. Income inequality is particularly notable and it has among some of the highest poverty rates in the world.

Contents

- 1 Etymology

- 2 History

- 2.1 Prehistory

- 2.2 Proto-Creeperian civilization

- 2.3 Creeperian Confederation

- 2.4 Kingdom of Creeperia

- 2.5 Emirate of Rabadsun

- 2.6 Creeperian Crusade

- 2.7 Medieval monarchy

- 2.8 First Parliamentary Era

- 2.9 Inter-Parliamentary Era

- 2.10 Second Parliamentary Era

- 2.11 Creeperian Civil War

- 2.12 Modern Creeperopolis

- 3 Geography

- 4 Government and politics

- 5 Economy

- 6 Infrastructure

- 7 Demographics

- 8 Culture

- 9 See also

- 10 Notes

- 11 References

- 12 Further reading

- 13 External links

Etymology

The name of Creeperopolis (Creeperópolis) derives from Creeperia (Ցրեէպըռիա), the name of a kingdom which existed from 537 to 745 in modern-day northeastern Creeperopolis, and the Eleutherian suffix —opolis (—όπολις), meaning "city". Creeperia translates as "place of the Creeperans" from the Old Creeperian language; the origin of the name "Creeperans" is unknown, but it has been theorized to mean "River People", in reference to the Xichútepa River, which was the primary source of water for the civilization. The suffix of —opolis was applied to the name Creeperia to form "Creeperopolis" in the 1200s; at the time, the Creeperans began a crusade against their Islamic rulers and applied the suffix to relate their struggle to that of an ancient Eleutherian legend of the city of Mégistopolis, which overthrew its tyrannical ruling class in the 279 BC. The Creeperans at the time wanted to relate their struggle to that of Mégistopolis, and named their kingdom "Creeperopolis".

By the mid-1300s, Creeperopolis was a large kingdom which encompassed much of central Sur, but the suffix —opolis remained. Since the 1800s, there have been some efforts to rename the country back to Creeperia and remove the —opolis suffix, but those efforts failed to gain much popular support. "Greater Creeperopolis" (Creeperópolis Mayor) has been another name suggested as an alternative to only "Creeperopolis".

History

Prehistory

Archaeological research indicates that the first humans arrived in modern-day Creeperopolis around 24,000 years ago, with the oldest human remains being found in the modern-day department of San Romero near the San Romero River (previously known as the Xichútepa River). Historians believe that the first humans arrived by boat from modern-day Montcrabe through the Bay of Salvador, as a crossing of the Creeperian Range is considered to be unlikely.

Archeological sites dating from 26,000 BC to 2500 BC have been categorized as being prehistoric Creeperian. The site of the prehistoric Creeperans have yielded human remains, animal remains, preserved homes and tools, and remnants of cave art. Among the animal remains discovered at the various sites were those of domesticated mammals and now-extinct reptiles. The majority of prehistoric Creeperian sites were discovered between the 1950s and 1970s when the country engaged in many large-scale construction projects. Most prehistoric Creeperian sites are located in the modern-day departments of Cantoño, La'Libertad del Norte, Salvador, and San Romero.

Around 3500 BC, an event known as the prehistoric-Creeperian diaspora occurred when prehistoric Creeperans migrated out of modern-day San Romero. Groups of prehistoric Creeperans migrated south into modern-day southern Creeperopolis, western Creeperopolis, and Sequoyah; the descendants of these migrants include the Castillianans, Rakeoians, Senvarians, and Sequoyans. Around the same time, another group of Creeperans migrated east. They traveled by boat; most settled in modern-day eastern Creeperopolis, while others travelled across the Southern Ocean and eventually reached modern-day Lurjize and the San Carlos Islands. The descendants of these migrants include the Atlántidans, the Lurjizeans, and the Native San Carlos Islanders. The reason for this mass migration from Creeperopolis remains unknown, but is speculated to most likely be a result of the need for more land.

Proto-Creeperian civilization

In 2500 BC, the first known use of written language was recorded in Creeperopolis, marking the beginning of the proto-Creeperian civilization. During the first third of this period from 2500 BC to 1650 BC, known as the Inalikauitl (Pre-Old Creeperian for "Early Period"), the Creeperans were organized into city-state-like communities along the banks of the Xichútepa River and the shore of the Bay of Salvador. The reason for the rise of the city-states during this period is unknown. Although the city-states were organized into small local chiefdoms, there was no central authority which spanned across the entire civilization from western Cantoño to southern La'Libertad del Norte.

The Ueykauitl ("Great Period") began in 1650 BC, the year that the first true nationstate arose in the proto-Creeperian civilization: the Kingdom of Xichútepa. The kingdom, which many scholars believe is legendary or even mythical, is said to have been founded by Huitzilopochtli, who was the god of the Sun, the god of war, and the god of the gods of the Creeperian pagan religion. He established the title of tlatoani ("one who rules") and reigned until his death in 1611 BC. He was succeeded by Tezcatlipocachtli (1611BC – 1584 BC) and then Chicomexochtli (1584 BC – 1578 BC).

The Kingdom of Xichútepa ended in 1578 BC it was overthrown by the Kingdom of Cuscatlán which was established by Topiltzin in 1580 BC; Topiltzin was a cousin of Chicomexochtli and is traditionally believed to be the ancestor of all Creeperans alive today. The kingdom's first thirteen kings from Topiltzin I (1580 BC – 1551 BC) to Tecpancaltzin IV (1270 BC – 1233 BC) are only known through the Great Lineage of Tlatoanis, a list of the kings of Cuscatlán produced during the 2nd century BC; no archeological evidence from any of their reigns has been found. Tlatoani Topiltzin VI is the first ruler of Cuscatlán with attested archeological evidence, as a statuette of him dating to the 15th year of his reign, 1218 BC, was found near the city of Santa Rosa in 1956.

Topiltzin VI was deposed in 1199 BC and replaced by Tlacomihua I, beginning a 73-year period of military dictatorship known as the Inauatil in Teyaochiuanimeh ("Rule of the Warriors" or "Rule of the Generals"). Hereditary monarchial rule was established by Mixcoatl I in 1126 BC, and his descendants ruled until 888 BC—with an interruption between 1040 BC and 999 BC—when they were deposed by Kukulkan I. His son, Kukulkan II, was the last ruler of the Kingdom of Cuscatlán, as a civil war fractured the kingdom in 867 BC, ending the Ueykauitl, although Kukulkan II's descendants continued to rule the rump state of the Kingdom of Tsakinatil until 620 BC.

The fall of Cuscatlán led to the beginning of the Tsakikauitl ("Late Period"), where various kingdoms arose in the territories which were held by Cuscatlán. Among the most powerful kingdoms of the Tsakikauitl include the Kingdom of Metapán, the Kingdom of Izalco, and Kingdom of Nahuizalco, and the Kingdom of Apaneca, and are collectively considered to be "Four Great Kingdoms". The period is known for its general instability, as warfare existed among the various kingdoms which were attempting to reestablish a domain with the same size and power of the Kingdom of Cuscatlán. Additionally, Apanecan and Nahuizalcan records dating to the 6th century BC describe a large scale invasion from a group of people known as the Uitstlanik Tlakah ("Southern Peoples"); there is little to no information or archeological evidence to determine who these invaders were, but it is generally believed that they may have been the proto-Senvarians.

In 250 BC, the Tsakikauitl and the proto-Creeperian civilization as a whole came to an end as a result of the eruption of the Chicxulub volcano. The plinian erupted, ranked as a level 7 or super-colossal eruption, completely destroyed the volcano, leaving behind a caldera lake where volcano once stood. An estimated 32 cubic miles (133 cubic kilometers) of volcanic ash were ejected into the atmosphere, burying the surrounding area under a layer of ash which was 45 feet (14 meters) deep. Additionally, the eruption resulted in a shift in global weather patterns, leading to decreased global temperatures over the succeeding two years.

The eruption caused famines across the proto-Creeperian civilization due to widespread crop failures and led to many wars waged by the various kingdoms to secure themselves food and supplies amidst the eruption. The amount of people who were directly killed by the eruption is unknown, but is believed to range in the thousands, and that hundreds of thousands more died as a result of the ensuing famines and wars. Very little information is known from this period, and is sometimes referred to as the "Creeperian Dark Age". By 220 BC, historians believed that "effectively all" of the kingdoms of the Tsakikauitl and reduced the surviving Creeperans to being organized into local tribal chiefdoms.

Creeperian Confederation

In 220 BC, after what is believed to have been a 30-year period of warring between various tribes following the fall of the proto-Creeperian civilization, seven tribes—the Amacha, the Chihueta, the Iloqutzi, the Imnoqueti, the Llohechue, the Tzachu, and the Xuhuetí—formed a loose military alliance between themselves and established a de facto political entity among themselves called the Cuēpieopoxūeta ("Land of the Creeperans"), referred to by modern historians as the Creeperian Confederation. Its capital city was selected to be Xichútepa (not related to Old Xichútepa, the capital city of the Kingdom of Xichútepa), which was also the capital city of the Chihueta. Although each tribe was lead by a tlatoani, the confederation was collectively led by a leader known as the tlen se tlatoani ("first one who rules"), and the first tlen se tlatoani chosen by the confederation was Machtitín I of the Chihueta.

From 200 BC to 145 BC, during the reigns of Machtitín I, Machtitín II, Xipilli I, and Xiuhcoatl I, the Creeperans constructed the Great Pyramid of Xichútepa, the largest pyramid in the world by volume and surface area. The pyramid served as the religious center of the confederation, and was the primary location where humans were sacrificed by Creeperian pagan priests to their gods. Additionally, beginning in 139 BC, the pyramid was also the location where the confederation's quasi-government distributed grain and food to Xichútepa's poorest residents, known as the Imakaka in Sentli ("Giving of the Maize").

During the construction of the pyramid, Xiuhcoatl I began a war against the Atlántidan Confederacy after a series of Atlántidan raids on Amacha towns and cities, including Tecuauh which was sacked in 154 BC. The Creeperans fought a series of battles in the Atlántidan Peninsula against the Atlántidans led by Cahualan. After a final defeat at the Battle of Acatepec in 151 BC, Cahualan and the remaining Atlántidan forces fled south of the Sil River, which demarcated the southernmost extent of the Atlántidan Confederacy resulting in its effective dissolution. The Atlántidans captured during the war were used for slave labor and sacrificed. The Creeperans would continue to raid and attack Atlántidan territory south of the Sil River until 540 AD to capture more slaves to be used in construction projects and to be sacrificed.

The Creeperian Confederation came under threat of invasion in late-111 BC when three legions of the Romanyan Empire commanded by Quinctilius Varus, Marcus Caelius, and Servilius Geminus crossed the Creeperian Range on an expedition to survey the land south of the mountain range for a potential future military campaign and annexation. In May 110 BC, the Romanyan expedition was ambushed by the Creeperans during the Battle of the Xichútepa River, resulting in a decisive Creeperian victory and forced the Romanyans to withdraw, never again sending another expedition south of the Creeperian Range. The battle was led by Tlen se Tlatoani Chepín I and he had the surviving Romanyan captives sacrificed at the Great Pyramid of Xichútepa throughout the succeeding 30 years.

Chepín I had the longest reign of any Creeperian monarch, reigning for 68 years from 130 BC to 62 BC. Following his reign, nine of the last eleven tlen se tlatoanis had exceptionally long reigns; all of them reigning for over 50 years, and six reigning for more than 60 years. Historians attribute their longevity and long reigns due to the Creeperian tradition of selecting an eighteen-year old to be the next tlen se tlatoani, as the Creeperans worship eighteen primary gods, and that they were exceptionally cared for by their subjects throughout their lives.

Following the death of Ahuiliztli II in 520, the confederation fell into civil war, as six of the confederation's seven tribes selected Ozchaxar I to be the next tlen se tlatoani, while Ahuiliztli II's son, Ahuiliztli III of the tribe of Amacha, declared himself as the rightful tlen se tlatoani, wanting to return the confederation to a hereditary monarchy. The ensuing civil war, known as the War of Creeperian Unification, lasted until 537 with Ahuiliztli III' decisive victory at the Battle of Xichútepa which resulted in Ozchaxar I's suicide and the end of the Creeperian Confederation.

Kingdom of Creeperia

After his victory at the Battle of Xichútepa, which has been traditionally dated as 15 September 537, Ahuiliztli III proclaimed the establishment of a hereditary monarchy and united the seven tribes of Creeperopolis under one nationstate. The nation was called the Kingdom of Creeperia and was the first nationstate which had existed in the region since the end of the proto-Creeperian civilization. Xichútepa was declared as the country's capital city.

The kingdom and people continued to follow the Creeperian pagan religion until 540, only three years after the kingdom's establishment, when Pope Vigilius I arrived in the kingdom after being exiled by the Northern and Southern Romanyan Empires during the Great Schism of the Christian Church. Vigilius I managed to convert the Creeperian royal court, and soon, the kingdom's population was converted to Christianity. As a part of their conversion, many Creeperans adopted Hebrew, Eleutherian, and Romanyan names, including Ahuiliztli III, who changed his name to Filip upon his baptism. Additionally, he ordered the cessation of human sacrifices and abandoned the city of Xichútepa, including the great pyramid which was seen as a pagan monument. The sudden change in the country's religion incited an anti-Christian revolt which was suppressed by Filip I by 545. He established a new capital city called Yerkink (Old Creeperian for "Heaven") and he ruled from the city until his death in 568.

In 571, the kingdom came under threat by a joint-Northern and Southern Romanyan army which was sent to kill Pope Ioannes III in an effort to end the Great Schism. The Creeperans, led by Ioannes III and King Zinum I, prevailed as the victors of the Battle of the Three Popes, which resulted in the death of Northern Emperor Constans III and ended the Great Schism, when antipopes Ioannes III and Felix IV abdicated and recognized Ioannes III as the rightful pope. The battle is considered by historians to be the beginning point of the modern Creeperian Catholic Church, which remains Creeperopolis' official and dominant religion.

Zinum I was assassinated and usurped in 598 by his younger brother, Ferdinand I, but Ferdinand I was himself assassinated in 601 by Zinum I's son, Zinum II. He was succeed by his son, Zinum III, upon his death in 613, but Zinum III disappeared less than a year into his reign and was succeeded by his uncle, Filip II. Historians believe that Filip II killed Zinum III in a bid to ascend to the throne. Filip II was succeeded by his son, Rramiro I, who was the longest reigning king of Creeperia, reigning for 41 years from 659 to 700. He is considered to be the second most important king of Creeperia, after Filip I, for his contributions to recording the history of the Creeperian Confederation. During Rramiro I's reign, the Codex Amara was written which documents the history of the confederation from its establishment to its dissolution. Most of the current knowledge about the confederation is only known due to the codex, however, only around 50 to 60 percent of the codex have survived. He was succeeded by his son, Jeyms I, upon his death.

Throughout the kingdom's existence, its language shifted from Pre-Old Creeperian to Old Creeperian, but both languages were completely different from each other, not even belonging to the same language family. The Great Creeperian Language Shift remains a unsolved mystery within history and linguistics, but some scholars have proposed that a mix of Romanyan and southern Surian influence combined with the Pre-Old Creeperian language to form an entirely new language.

The kingdom's final ruler was Jentlmen II, who ascended to the throne in 732 after the death of his father, Jentlmen I. In 739, Creeperia was invaded by the Caliphate of Deltino, a nation of Islamic Arabs which was exiled from Ecros over Islamic theological disagreements. The Deltinians, led by Caliph Abdul Hazem II bin Abu Kharzan, and later Abdul Humaidaan I bin Abu Kharzan, invaded Creeperia to expand their domain and spread their sect of the Islamic religion. Assisted by Pashpanut, a cousin of Jentlmen II who sought the throne of Creeperia, the Deltinians captured Yerkink on 11 July 745, ending the Kingdom of Creeperia.

Emirate of Rabadsun

After the fall of Yerkink in July 745, Abdul Humaidaan I proclaimed the establishment of the Emirate of Rabadsun, a Creeperian-administered client state of the Caliphate of Deltino, and named Jentlmen II's younger brother, Rrudolf I, as its emir, instead of Pashpanut; after his installment as emir, Rrudolf I ordered the execution of Pashpanut for treason against his country and own family. Rrudolf I recognized Abdul Humaidaan I as his superior, and in 747, he changed his name to Rudulifu I to abide by the caliph's decree that all Creeperans must adopt Arabic or Arabic-translated names. The city of Yerkink was renamed to Rabadsun. Although the Deltinians defeated Creeperia in 745, some Creeperans continued to resist the Deltinians in the Xichútepa rainforest until the 1110s, even forming the rump state of Neo-Creeperia which existed from 767 to 1001.

Although the Deltinians' primary language was Arabic, they also introduced the Spanish language to the continent; Arabic was the caliphate's governmental and religious language and common among the ruling class, while Spanish was more commonly spoken by the poor and peasants. Over time, Spanish replaced Old Creeperian as Rabadsun's primary language, while at the same time, Arabic spread to all Deltinian social classes. The Creeperian dialect of Spanish completely replaced Old Creeperian by the 1000s, but the language continued to be used by the Church for religious purposes.

The emirate was ruled by the Amara dynasty until 1120, when Emiress Mariaan I—Creeperopolis' only ever female head of state—was deposed by her husband, Alfawnasu I, with the support of Caliph Salim III bin Abu Rahimi, who did want a woman to be the head of state of any of his client states. Alfawnasu I was a member of the Martiniz family, which traces its origins to the Emirate of Córdoba of the 600s; the family gained power in Rabadsun in the 840s after a war waged by Pelayo Martínez de Córdoba. The Martiniz dynasty held the position of emir until the emirate's abolition.

Throughout the existence of the Emirate of Rabadsun as a Deltinian client state, the Deltinians permitted all conquered peoples, including the Creeperans, to continue practicing their own religions, but offered tax exemptions to those converted to Deltinian Islam. Creeperans who converted to Deltinian Islam have since been referred to as Islapóstas (Creeperian Spanish for "Islamic Apostates"). This policy of tolerating non-Islamic religions within the caliphate's territories continued throughout its existence until October 1230, when recently installed Caliph Sulayman III bin Abu Arshad issued the One-Religion Decree, which mandated that all Deltinian subjects, including the Creeperans, must convert to Deltinian Islam or face a military response to force conversion or kill those who resisted.

News of the decree reached Rabadsun in January 1231, and the Creeperian Catholic Church invoked the Second Council of Rabadsun to discuss the consequences of the decree and what action should be taken. On 8 February 1231, Pope Jiryjuriun IX announced that the council had rejected the caliphate's decree and Emir Alfawnasu III declared independence for the Emirate of Rabadsun, renaming his domain to the Kingdom of Creeperopolis, beginning the Creeperian Crusade.

Creeperian Crusade

Upon the declaration of the kingdom of Creeperopolis, the Creeperian War of Independence began and an estimated 30,000 Creeperian rebels overpowered the Deltinian garrison in the city. Once the city was secured and the Deltinian military presence was destroyed, Alfawnasu III changed his name to Alfonso I, the name of the royal family from Martiniz to Martínez, and his title of emir to king. This was replicated by Pope Jiryjuriun IX, who changed his name to Gregorio IX, and the city of Rabadsun being renamed to Salvador (Spanish for "Savior", in reference to Jesus Christ). This policy of changing all Arabic names to Spanish names was known as the De-Arabization and was enforced to separate the newly established kingdom from their former overlords. The Deltinians responded to the Creeperian uprising, but following a second battle in Salvador in March 1231 and the Battle of Edfu in October 1231, Sulayman III formally recognized Creeperian independence. The kingdom's banner was the same as that of the emirate: a black and white swallowtail but with the central star and crescent removed.

In April 1231, around 200 Creeperian Catholics were killed in the city of Alqarya which resulted in the formation of the Creeperian Inquisition and the mass killings of Islapóstas within Creeperian territory. The deaths of the 200 in Alqarya reinforced to the Creeperian people that the conflict against the Deltinians was not only a war for independence and sovereignty, but also a religious war between Creeperian Catholicism and Deltinian Islam.

Following a failed failed invasion of Deltino led by Pedro Herrador Cestalles in 1233, Alfonso I led his own invasion from 1235 to 1237 resulting in moderate inland territorial gains. In 1241, Prince Emmanuel—a younger brother of Alfonso I—led a continued campaign south along the coast of the Bay of Salvador, but it ended in defeat and in Emmanuel's death in the 1244 Battle of Sohaq. Alfonso I led another invasion in 1247 to avenge his brother's death, resulting in victory and Creeperopolis severing the caliphate's access to the Bay of Salvador in 1253. In 1258, Creeperopolis ceded land near Salvador to the Creeperian Catholic Church, forming the State of the Church, a client state which served as the religious center of the Church.

Alfonso I led his final invasion of Deltino in 1256, but he died at the city of Idku during the campaign on 3 July 1264, and has been posthumously referred to as Alfonso the Great. He was succeeded by his son, Alfonso II, who negotiated a peace treaty with Deltinian Caliph Salim IV bin Abu Arshad—who succeeded Sulayman III following his death in 1263—and formally ended the state of war between the two countries. The Treaty of Idku was unpopular in both countries, resulting in rebellions in both countries against both monarchs; Izzat al-Toure led a failed rebellion in 1265 against Salim IV, resulting in his execution after the caliph recaptured Almadinat Almuqadasa (the Deltinian capital city), while Ramón Miaja Saravia led a failed rebellion in 1266 and 1267 against Alfonso II, which resulted in his execution at the Battle of El Chopo by Alfonso II. Both Alfonso II and Salim IV ruled until 1273, and during their reigns, no major war was waged during a period of six years known as the Paz Sureño Menor. The peace ended in 1273 after Salim IV was overthrown and killed by his son, Uthman I bin Abu Arshad, and Alfonso II abdicated in favor of his brother, Salvador I; both newly installed monarchs went to war in 1273 to reignite hostilities between Creeperopolis and Deltino, but it ended in stalemate after two inconclusive battles.

In 1280, Uthman I ordered an invasion of Creeperopolis and gave command of the invasion to Muhammad al-Saffah; he commanded a force of 50,000 soldiers and recaptured the city of Idku in 1281. From January 1281 to April 1281, al-Saffah marched his army along the Salvador River to the city of Salvador, known as the March of Terror, and besieged the city, but was forced to withdraw to Idku in June 1281. Al-Saffah was killed at Idku in 1284, and the ensuing peace treaty resulted in Deltino ceding the city of Dahanomah (modern-day La'Libertad) and access to the Bay of Atlántida to Creeperopolis.

Salvador I died in 1285, and his son and successor, Manuel I, launched an invasion of Deltino in August of that year. After defeating the outnumbering Deltinian army at the Battle of Alsakhra in November 1285, his invasion culminated in further territorial annexations around La'Libertad. Creeperopolis supported the Hondurans in a revolt against Deltino from 1288 to 1289, and further supported the newly established Kingdom of Honduras from 1289 to 1290 during a Deltinian attempt to reconquer the kingdom. A failed assassination attempt on Uthman I in 1290 by his eldest son, Uthman bin al-Arshad, left the caliph paralyzed for the rest of his reign until his death in 1295. Salim V bin Abu Arshad, Uthman I's second son and regent during the last five years of his reign, ultimately became his successor.

Manuel I died in a hunting accident in 1301 and was succeeded by his twelve-year old son, Miguel I. He declared his intentions to invade and destroy Deltino, but his regent, Pedro Candia Bolero, prevented him from doing so. In 1304, Miguel I was given his full powers as king, in December that year, he and Hernán Monroy Pizarro launched an invasion of Deltino. From 1304 to 1311, the Creeperans and resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Deltinians in indescriminate mass killings throughout the campaign. As his army reached the lake of Buhayrat Alrasul, Salim V met Miguel I at Najallah and offered peace and many concessions. Among the concessions included the ceding of all Deltinian territory north and east of the San Luísian Range and north of the Zapatista River, an annual yearly tribute, and the marriage of Iizabila al-Arshad, a daughter of Salim V, to Miguel I.

Salim V died in 1319 and was succeeded by his son, Salim VI bin Abu Arshad, who, although wished to regain much of the caliphate's lost lands, also wanted to prevent further wars with the increasingly powerful Creeperopolis. The news of Salim V's death emboldened Miguel I to bring an end to the Caliphate of Deltino once and for all, especially as his war and that of Manuel I exceptionally weakened the caliphate's military and economic power. Miguel I embarked on his second invasion of Deltino in 1231, capturing several cities along the coast of Buhayrat Alrasul throughout 1322, 1323, and 1324. The caliph sent a delegation to Miguel I offering more land and to spare Almadinat Almuqadasa; Miguel I ordered the executions of all but one of the delegates, and sent the sole survivor to inform the caliph that he would destroy the Deltinian capital. The Creeperans began besieging Almadinat Almuqadasa in 1324, and following two land battles and two sea battles, the Creeperans broke the city's defenses on 13 June 1326; they executed the caliph and his family, massacred over 200,000 of the city's inhabitants, and burned the city to the ground, leaving it in ruins. Miguel I established the city of La'Victoria on top of the ruins of Almadinat Almuqadasa and issued the Decree of La'Victoria, outlawing the practicing of Islam within his kingdom. All Deltinian Muslims within the kingdom, in what became known as the First Great Persecution (1326–1565), were killed, enslaved, or forced to convert to Creeperian Catholicism, with those converting becoming known as Murtamashin (Arabic for "Christian Apostates").

Following the death of Salim VI and the fall of Almadinat Almuqadasa, the Caliphate of Deltino collapsed and fractured into four rump states: the Aljanub Caliphate led by Yusuf I al-Dhahir bin al-Janub, who was recognized as caliph, the Emirate of Abdan led by Harun al-Azimi, the Emirate of Helam led by Muhammad al-Salim, and the Emirate of Jakiz led by Hisham al-Ishaaq. The caliph and three emirs waged war against the Creeperans from 1327 to 1331, but it ended in their defeat following the fall of Qalajanubia and the death of al-Dhahir. The Aljanub Caliphate was annexed by Creeperopolis and the three surviving emirates were forced to pay tribute to Creeperopolis. Eventually, Helam was conquered in 1334, Abdan was conquered in 1336, and Jakiz was conquered in 1345; the Siege of Shata' Albahr ended on 25 December 1346, marking an end to the Creeperian Crusade and the end of 611 years of Deltinian rule in Sur.

Medieval monarchy

Following the fall of the Deltinian rump states, Miguel I focused on continuing Creeperopolis' expansion. In the 1350s, he sent expeditionary forces west of the Zapatista and along the modern-day San Salvador River, west of the San Miguel River into Honduran territory, and east into the Atlántidan Peninsula. After a war against the Hondurans 1357 to 1360, Honduran King Vitruvio III was deposed and the kingdom was reorganized into the Principality of San Miguel. That same year, the Creeperian conquests in Atlántida were organized into the Principality of La'Libertad del Sur. The Kingdom of Granilla, located on the island of San Pedro, was conquered in 1363.

Miguel I died on 27 April 1365, having reigned for over 64 years. He was succeeded by his son, Adolfo I, who brought a period of peace to the kingdom, beginning the period known as the Paz Sureño Mayor (Major Surian Peace). During this period, the kingdom focused on arts, literature, and science in what has since been referred to as the Creeperian Golden Age. Additionally, the voyages of Cristóbal Colón Cámarillo occurred during the 1380s which claimed the San Carlos Islands for Creeperopolis. The golden age and the period of peace ended in 1384 when Deltinians rose up in rebellion in southern Creeperopolis. Adolfo I died during the first year of the rebellion, and his son, Miguel II, crushed the rebellion by 1385, leading to the deaths of up to 200,000 Deltinians. After a generally peaceful reign, Miguel II died in 1405 and was succeeded by his son, Miguel III.

Miguel III wished to initiate a new period of Creeperian expansion, beginning with the dissolution of the Principality of San Miguel, formally annexing it to the kingdom in 1405. Creeperian armies expanded control all the shores of Lake San Salvador throughout the 1410s in an effort to quell piracy on the lake. Additionally, the principalities of San Salvador and Santa Ana were established in 1412, and the Principality of Nuevo San Salvador was established in 1419, greatly expanding Creeperopolis' influence in central Sur. Wars of submission were waged in the San Carlos Islands against the native islanders to enforce Creeperian control of the islands. Similar to the establishment of the captaincy general of the San Carlos Islands, Rear Admiral Gustavo Hurtado Mendoza, the captain general of the San Carlos Islands, conquered the islands of Lurjize and established the Captaincy General of San Esteban in 1423.

The Creeperian expeditions into the Atlántidan Peninsula upset the native Atlántidans, who along with many peasants across the kingdom, rebelled against the monarchy. Although the rebellions in Creeperopolis were suppressed and killed over 500,000 peasants, the Atlántidans achieved independence and established the Kingdom of Atlántida, ending the Principality of La'Libertad del Sur and Creeperian control in the peninsula. Additionally, the principalities of San Salvador and Santa Ana were dissolved and incorporated directly into the kingdom to better assert control over those areas, as many of the uprisings during the war were concentrated in those principalities. The Principality of Nuevo San Salvador was later annexed in 1445.

On 1 January 1445, Miguel III and most of the royal family were massacred in Salvador under the orders of Pánfilo Kassandro Rodríguez, who was dissatisfied with the result of the Creeperian Peasants' War and attempted to usurp the throne. His attempt failed, however, after one of Miguel III's surviving sons, Manuel II, ascended to the throne and had Kassandro Rodríguez tortured to death. From 1454 to 1456, the Creeperans waged war against the Kingdom of Senvar, annexing the kingdom in 1456. Manuel II was succeeded by his son, Miguel IV, in 1487, upon which, Deltinians in southern Creeperopolis rebelled; the rebellion lasted ten years, but it ended as a failure and resulted in the deaths of 400,000 Deltinians. Miguel IV was found dead in the Salvador Royal Palace on 1 September 1500, with the modern consensus believing that he was secretly assassinated by his son and successor, Miguel V; the king instead blamed the assassination on his younger brother, Prince Alfonso, who was forced to flee to exile in Atlántida, but was eventually assassinated in 1516 by assassins sent by Miguel V.

During the first years of his reign, Miguel V committed various atrocities against Creeperian peasants for his own amusement, had various affairs with multiple women, and fathered at least nine illegitimate children. His actions, which were seen as immoral and un-Christian, led to the Protestant Reformation within Creeperopolis, as the Church seemed to not take action against the king. Protestants, as well as Deltinian Muslims, across Creeperopolis rose up in rebellion against the monarchy and the Church in 1603, and the ensuing Twenty Years' War resulted in the deaths of over 5 million people. The Protestant rebellion failed by 1623, with many of its leaders being killed and Creeperian Protestantism eventually being eradicated. During the war, Senvar regained its independence in 1504 and Miguel V failed to reconquer it.

In 1535, Miguel V ordered the genocide and ethnic cleansing of the Honduran people, who he blamed for the death of his wife. Modern historians have viewed Miguel V's decision to massacre the Honduran people and indicating that he suffered from some sort of mental illness which deteriorated his sanity and made him an exceptionally cruel ruler. The Honduran Genocide is considered to be an example of a "successful genocide", as it resulted in the deaths of 1.2 to 1.6 million Hondurans. Although some Hondurans survived the genocide, the group's population was devastated and has never recovered to its pre-genocide numbers.

Miguel V's reign was viewed as extremely autocratic, and two assassinations were attempted in 1536 and 1547 by Creeperian nobles who opposed his reign; large purges and mass executions ensued following both failed assassination attempts on the direct orders of Miguel V. He was eventually assassinated by the Royal Guard on 1 September 1555, exactly 55 years after he assassinated his father and assumed the throne. He was briefly succeeded by his son, Miguel VI, for two days, until he himself was assassinated by the Royal Guard. He was replaced by Alfonso III, the son of Miguel V's exiled brother, Prince Alfonso. Alfonso III renamed the royal title of "King of the Creeperans" to "King of Creeperopolis" to distance himself from his uncle's reign.

First Parliamentary Era

Many Creeperian nobles feared the power of the monarchy as a direct result of Miguel V's reign and began attempting to curb its power as much as power. From 1555 to 1565, Alfonso III struggled with Creeperian nobles for power and influence within the kingdom which culminated during the Surian Revolutions of 1565, where as later occurred in the kingdoms of Atlántida and Castilliano, the nobles forced the king to relinquish his absolute powers and establish a democratically elected body to rule the country.

In January 1565, Creeperopolis' first ever democratic election[note 2] was held which elected 100 members to the country's parliament. The Conservative Party (PC) won 67 seats, while the opposing Liberal Party (PL) won 33 seats. The parliament officially formed on 8 March 1565 and Alfonso Moreno Salinas was elected as the country's first prime minister; the country became a constitutional monarchy, with executive power lying with the prime minister and the king becoming a figurehead. The following year, Creeperans across the kingdom held gubernatorial elections for each of the country's departmental captain generals (governors).

The Conservatives, although opposing the power of the monarchy, continued to support the monarchy's existence as a figurehead and wanted the Church to maintain significant influence over Creeperian society. Meanwhile, the Liberals held some radical positions for the time, such as secularization and the separation of Church and state, the expansion of suffrage to all landowning men, and some even more radical Liberals even proposed the abolition of the monarchy. To prevent the radical Liberals from legally abolishing the monarchy, the Conservatives and the moderate Liberals passed the Monarchal Protection Act in 1566 which amended the country's constitution to expressly declare that the abolition of the monarchy was considered to be a seditious act.

In 1569, the constitution was amended to declare that all future parliamentary and gubernatorial elections would occur concurrently every five years on the second Saturday of January, with parliamentary and gubernatorial terms beginning the 8 March following the election. In the 1570 general election, the Conservatives maintained a majority in the parliament, winning 61 seats. Moreno Salinas stated that he would not seek a second term as prime minister, and was succeeded by Bernardo Funes Luque on 8 March 1570. He was succeeded by his bother, Camilo Funes Luque, in 1580. The Conservatives held their majority in the parliament until 1600, when the Liberals won 53 seats in the 1600 general election and elected Emmanuel Sánchez Andino as prime minister. Many Conservatives and monarchists feared that the Liberals' rise to power would lead to the abolition of the monarchy, but Sánchez Andino reaffirmed that he would not seek to violate the Monarchal Protection Act. In 1611, Sánchez Andino ordered the military occupation of the Quebecshirite port city of Port François (which was ceded to Quebecshire in 1311) in support of the Quebecshirite Republican Assembly (ARQ) during the Quebecshirite Civil War; the territory was later formally returned to Creeperopolis in 1624.

Sánchez Andino was succeeded by Orlando González Leoz in the 1615 general election, but he died three years into his premiership. He was succeeded by Fidel Moreno Dávalos who served until his own death in 1636, and upon when he was succeeded by his brother José Moreno Dávalos, who served until 1670. After 70 years of Liberal rule, the Conservatives won the 1670 general election, and Alexander Carpio Maroto served as prime minister until 1695. Liberal Salvador Cerén Collazo served as prime minister from 1695 to 1725, when he retired from politics, and he was succeeded by Orlando Moreno Hidalgo. Moreno Hidalgo was an overt republican and anti-monarchist, and his anti-monarchist rhetoric worried Conservatives that he would openly violate the Monarchal Protection Act.

On 4 July 1729, monarchists launched a revolution against Moreno Hidalgo's government, attempting to depose him and dissolve the parliament. The uprising killed 25 people, including three members of parliament, but ultimately failed with many of the participants being arrested. Although there was no evidence that King Carlos III played a role in the uprising, Moreno Hidalgo had the king arrested, found guilty of seditious conspiracy, and executed on 13 August 1729. Upon the execution of Carlos III, Moreno Hidalgo announced the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of republic and moved the country's capital city to Adolfosburg, considered to be a bastion of liberalism in Creeperopolis.

The proclamation of a republic immediately incited a civil war between Conservatives—who supported Carlos III's younger brother, Adolfo II, as the king of Creeperopolis—and Liberals—who supported Moreno Hidalgo's republican reforms. Despite the hostilities between both groups, the both participated in the 1730 Creeperian general election to elect all 100 members of the parliament and to elect the president of Creeperopolis. Moreno Hidalgo ran as the Liberal candidate for president, while Adolfo II ran as the Conservative candidate with the intention of reestablishing the monarchy through democratic means. The election resulted in the Liberals both the presidency and the parliament, and the Conservatives continued their war against the Liberal government. With the Conservative resistance to the result of the election, Moreno Hidalgo annexed the State of the Church on 1 February 1730 and exiled Pope Benedicto XIII from the country, who died only 21 days later.

The civil war ended in 1741 with the signing of the Treaty of Adolfosburg. The treaty resulted in the abolition of the republic and the presidency, the restoration of the monarchy and the acknowledgement of Adolfo II as king, and Moreno Hidalgo's return to the premiership; the treaty also gave amnesty to all combatants, effectively returning Creeperopolis to the status quo before the war. Although neither the Conservatives or the Liberals got what they wanted, the Conservatives were more content with the outcome of the war; Moreno Hidalgo lost much of his support and popularity among Creeperian republicans who believed that he stopped the country's progress, while culminated in his suicide in office in November 1749. Moreno Hidalgo was succeeded as prime minister by Francisco López Yagüe, who previously served as prime minister from 1730 to 1741 when Moreno Hidalgo was president.

The Liberals lost the 1750 general election and the Conservatives elected Salvador Funes Tafalla as prime minister; he previously served as the Conservative's prime minister from 1730 to 1741 in opposition to López Yagüe. The Liberals won the 1765 general election and López Yagüe was reelected as prime minister, but he died 127 days into his term and was succeeded by Fernando Moreno Juderías. He was a son of Moreno Hidalgo and he held many of the same political positions as his father. The Conservatives feared that Moreno Juderías would attempt to reestablish the republic and launched another attempted coup against the government.

On 4 July 1771, monarchists, this time with the direct support of King Manuel III, launched another revolution against the Liberal government. This time, the revolution succeeded; all the Liberal members of parliament, including Moreno Juderías, were executed, and they proclaimed the reestablishment of absolute rule to the monarchy. The Supreme Court attempted to stop his actions, but Manuel III ordered the arrest of all the court's members and had them imprisoned, abolishing the court in the process. On 4 May 1778, Manuel III proclaimed himself as "emperor of Creeperopolis", marking the beginning of the Empire of Creeperopolis. In June 1778, he moved the country's capital to San Salvador and he ceded land to the Church south of the new capital city, reestablishing the State of the Church.

Inter-Parliamentary Era

Manuel III died on 12 November 1783 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Manuel IV, however, another of his sons, Salvador III, challenged his brother's claim to the throne, beginning a war of succession. The war ended in 1783 with the assassination of Salvador III and the exile of his family to Atlántida. Manuel IV ruled as an autocrat during a 50-year period known as the Manuelisto where he held absolute power. He attempted to implement various reforms to help consolidate his power, such as religious reforms to give the government more control over the Church and economic reforms to have more control over the economy.

By the 1820s, Creeperopolis began a slow period of decline and some democratic movements began to appear, calling for the reestablishment of a parliamentary system. Manuel IV cracked down on these democratic movements, but other movements against his government also manifested, such as workers strikes, Deltinian separatist movements, and republican protests. In June 1833, fearing that military officers were conspiring a coup against him, Manuel IV fired several army officers, including Adolfo Martínez Llachaumán, a grandson of Salvador III who was personally welcomed into the army by Manuel IV. The firings sparked a nation-wide army mutiny and the country's military officers deposed and killed the royal family, including Manuel IV.

Martínez Llachaumán was proclaimed as Emperor Adolfo III, and although some officers attempted to use him as a puppet ruler, Adolfo III quickly seized absolute control over the country and sidelined those he saw as a threat to his rule, beginning a 54-year period known as the Adolfisto. Among one of his first actions was the reversal of many of Manuel IV's policies, granting greater liberties to the Church and to aristocrats who controlled much of the country's land. This led to various rebellions across the country against his rule as well as the declaration of secession of some of the country's departments; all the rebellions and secessionist states were crushed by 1835.

Adolfo III called for the industrialization of Creeperopolis, publishing a manifesto titled the "Creeperian Investment into Natural Resources Gifted by God" which called upon the country's workers to "exploit the resources gifted to the Fatherland by God"; he established the National Mining and Smelting Corporation (CORNAMIF) to realize his manifesto. He is generally considered to be the monarch who began Creeperopolis' rise to becoming a regional power due to his industrialization efforts.

As a military officer, Adolfo III greatly expanded the country's focus on the military, expanding it significantly and formally introducing conscription. Under Adolfo III, Creeperopolis supported the Castillianan government of Caudillo Maximiliér Sauléu e Dóna during the Great Surian War from 1837 to 1843, but withdrew support before Castilliano's eventual defeat. During the war, Creeperopolis went to war with Ajakanistan from 1836 to 1837; conquered the Kingdom of Rakeo in from 1838 to 1840, forming the Captaincy General of Rakeo; and annexed Senvar in 1839, beginning the First Senvarian Insurgency which lasted until 1857. He also oversaw the establishment of a territorial claim in Tierrasur, named Adolfo III Land after himself.

Throughout his rule, Adolfo III harshly suppressed Senvarian culture and language in an attempt to destroy the Senvarian identity and assimilate them into the Creeperian culture. The resistance to his efforts culminated in the outbreak of a second insurgency in 1878 which persisted until 1888, after Adolfo III's death. Many Senvarians believed Adolfo III to be a traitor, as his mother was the daughter of Senvarian King Ninapakcha I and he swore to King Ninapakcha III that he would guarantee Senvar's independence upon the outbreak of the Great Surian War in 1836. He also swore to defend the Kingdom of El Salvador's independence during the war, but later conquered the kingdom in 1858; although King Josep II was not deposed, he was reduced to a puppet ruler under the newly-established the Captaincy General of Nuevo Honduras.

Adolfo III is considered by historians to be the most powerful monarch in Creeperian history, but by the end of his reign, he began to face various democratic movements which called for the restoration of the parliamentary system, the same situation which was faced by Manuel IV towards the end of his reign. Adolfo III refused to negotiate with the movement's leaders and imprisoned many, including Inhué Ordóñez Yepes who was considered to be the movement's leader. Adolfo III died in December 1887, and fearing a total democratic revolution against the monarchy, Adolfo III's successor, Maximiliano II, agreed to release Ordóñez Yepes and come to an agreement to reestablish Creeperian democracy.

Second Parliamentary Era

After a few days of negotiations between the monarchy and democratic activists, the two factions agreed to reestablish the country's parliament and return to constitutional monarchy. General elections were rushed in mid-December 1887 to elect a provisional 100-seat session of parliament; the election resulted in a victory for the center-left National Liberal Party (PLN)—which claimed to be the successor of the first parliament's Liberal Party—winning 56 seats. The opposition consisted of 34 members of the center-right National Conservative Party (PCN)—the claimed successor of the first parliament's Conservative Party—and 10 members from the right-wing Catholic Royalist Party (PRC), a splinter group of the National Conservatives.

The first session began on 31 December 1887 and Ordóñez Yepes was elected as the country's first prime minister in over 116 years. In 1888, a left-wing splinter of the National Liberals formed: the Creeperian Socialist Party (PSC) led by Édgar Cazalla Beldad. One month later, a far-left group splintered from the Socialists: the Creeperian Social Communist Party (PCSC) led by Mauricio Tasis Quesada, Prior to the 1892 general election, the parliament decided to increase the number of seats to 230. Additionally, the country's right-wing parties formed the Creeperian Conservative Coalition (CCC) and the country's left-wing parties formed the People's Social Coalition (CSP). As the Creeperian parliament was being organized, Nuevo Honduras became the independent state of El Salvador led by President Lluís Altayo Ramió of the left-wing Party of the Salvadoran People (PPS).

The CCC obtained a majority in the 1892 election and National Conservative Macos Espiga Mina was elected as the country's prime minister, however, he faced resistance from the Catholic Royalists who demanded important positions in the parliament in exchange for their support for Espiga Mina's premiership. The CCC retained its majority in the 1897 general election and Espiga Mina was elected to another term as prime minister, but he again faced resistance from the Catholic Royalists who had won almost 50 seats; the Catholic Royalists only approved Espiga Mina's election after seven ballots when the National Conservatives agreed to appoint Francisco Dueñas Díaz—the PRC's chairman—as 1st secretary and Antonio Sáenz Heredia—the PRC's deputy chairman—as 3rd secretary.

In the 1902 general election, the CCC again retained its majority, but the Catholic Royalists surpassed the National Conservatives as the largest member of the CCC. As such, Sáenz Heredia, who succeeded Dueñas Díaz as the party's chairman—and later caudillo—in 1901, was elected as the country's prime minister. Sáenz Heredia's premiership began a period of democratic backsliding which persisted throughout the remainder of the Second Parliamentary Era; among some of his actions included amending the country's constitution to prohibit the prosecution of incumbent members of the parliament, which many at the time viewed as him protecting himself and his allies from prosecution from illegal actions they would commit while in office.

The CCC lost the 1907 general election to the CSP, which elected Ordóñez Yepes as prime minister. He attempted to undo many of Sáenz Heredia's policies, but he did not have enough support from the more radical factions of the CSP who wanted to maintain their own legal immunity for similar reasons the PRC wanted their immunity. The 1912 general election is widely considered to have been rigged in favor of the PRC due to the party funneling bribes to many electoral officials, and Sáenz Heredia was elected as prime minister. Additionally, five seats were added to the legislature. Although the PRC remained the largest party, the CSP obtained a majority in the 1917 general election and Ordóñez Yepes was again elected as prime minister. During Ordóñez Yepes' third term, the captaincy generals of Rakeo and San Esteban gained their independence in 1918, forming the modern states of Rakeo and Lurjize, respectively.

Ordóñez Yepes died during his third term in 1921 and was succeeded by Cazalla Beldad, which caused controversy among the CCC which feared that this would lead to a surge in leftist votes. Although the CCC won the 1922 general election and Sáenz Heredia was elected as prime minister, the Socialists surpassed the National Liberals to become the legislature's second largest party; the National Liberals and the National Conservatives were eclipsed by their more ideological splinter groups as the country's two largest parties.

During his third term, Sáenz Heredia crushed two attempted revolutions: the first in 1923 by the far-right Creeperian Pro-Fatherland Front (FPPC) which attempted to overthrow the government and establish a fascist dictatorship, and the second in 1925 by the far-left Action Party for Granilla (PAG) which attempted to achieve independence for the department of San Pedro. His third term also saw the heightening of the Reigns of Terrors, an ideological paramilitary conflict between the far-right Camisas Negras (CN) paramilitary of the Pro-Fatherland Front, the far-right Falange Creeperiano (FALCRE) paramilitary of the Catholic Royalists, and the far-left Atheist Red Army (ERA) of the Social Communists.

The CSP won the 1927 general election, and instead of selecting a member of the National Liberal Party, the coalition elected the Socialists' Cazalla Beldad as the country's prime minister, making him the first Socialist elected to the office. His election led to outrage among the far-right, who assassinated Cazalla Beldad on 7 February 1928 by the Camisas Negras. Although Sáenz Heredia attempted to seize power, he was eventually replaced by Social Communist Joel Lacasa Campos, the first far-leftist to hold the office. In retaliation for Cazalla Beldad's assassination, the Atheist Red Army assassinated Gustavo López Dávalos, the CEO of the National Coffee and Sugar Corporation (CORNACA), on 23 February 1928. López Dávalos had hired the Camisas Negras to assassinate Cazalla Beldad due to his frustration regarding the enforcement of the Act to Protect the Workers of Creeperopolis. In retaliation for López Dávalos' assassination, the Falange Creeperiano assassinated Lacasa Campos at his home on 1 March 1928. They also attempted to assassinate Cayetano Handel Carpio, the leader of the Atheist Red Army, that same night, but he was not home when they attacked and killed his family.

In response to the unfolding political crisis, newly elected National Liberal Prime Minister Tobías Gaos Nores declared martial law and ordered the military to forcefully crush the paramilitary violence between far-right and far-left. The crisis officially ended in April 1928, but no one was prosecuted for their roles in the crisis. Gaos Nores and Minister of the Treasury José Pardo Barreda were involved in a corruption scandal in 1932, and shortly after the scandal broke, Gaos Nores reportedly died of Creeperian Malaria, although, many believe that he actually committed suicide.

Creeperian Civil War

The CCC won the 1932 general election, and Sáenz Heredia was elected to a fifth term as prime minister, although, the CSP only recognized it as his fourth term. By then, the moderate National Liberal and National Conservative parties were reduced to a combined 17 seats, while the more extreme Catholic Royalist and Socialist parties controlled 215 of the parliament's 245 seats.

On 2 January 1933, Emperor Adolfo IV died at the San Salvador Imperial Palace to Creeperian Malaria, and his death resulted in a power struggle for the throne between two of his sons: Romero I and Miguel VII. Both declared themselves to be the country's legitimate emperor; Romero I was supported by the CCC due to his traditionalist and conservative beliefs, while Miguel VII was supported by the CSP due to his secular and Marxist beliefs. Later that night, factions of the army loyal to both brothers clashed at barracks in San Salvador del Norte, beginning the Creeperian Civil War.

The faction which supported Romero I established the Catholic Imperial Restoration Council (CRIC) and are commonly known as the Romerists; Sáenz Heredia was the council's prime minister, and Adolfo Cabañeras Moreno was its minister of defense and Supreme Caudillo. The faction which supported Miguel VII established the National Council for Peace and Order (CNPO) and are commonly known as the Miguelist; Rolando Rubio Noboa was the council's prime minister, and Juan Salinas Figueroa was its minister of defense and Supreme Caudillo.

For most of the civil war, the north, center, and west were controlled by the Romerists, while the south and east were held by the Miguelists. The territories under their control were fiercely ruled with all political opposition being suppressed. Many people were killed during the White and Red Terrors, respectively; the Romerists targeted communists and atheists, while the Miguelists targeted fascists and Catholics. The atrocities committed by the Miguelists are considered to be particularly organized and have been described as a genocide. The De-Catholization is described as having been the deliberate attempt to exterminate the Church from the territories controlled by the Miguelists which resulted in the deaths of an estimated 9 to 11 million people. Additionally, both factions targeted the Deltinians, such as the 1944 Denshire massacre committed by the Romerists and the 1937 Deltinian massacre committed by the Miguelists.

Both factions received internal and external support for their causes. The Romerists received internal support from the Crusaders of King Alfonso (FCPC) self-defense militias, commonly known as the Cristeros, and the Militarist Nationalist Front (FRENAMI) death squad. They received foreign backing from Atlántida, Castilliano, El Salvador (which later became a Creeperian client state in 1935 under the rule of Carlos Castillo Armas), Quebecshire, Salisford, and the State of the Church. The Miguelists received internal support from the Senvarian Liberation Front (KSK), a Senvarian separatist group which declared independence as the Kingdom of Senvar in 1934, and the Apostates for the Cause (APÓCA) self-defense militia. They received foreign backing from Ajakanistan, Granada (a Miguelist client state in El Salvador from 1933 to 1935), and Terranihil.

Some of the civil war's largest and most important battles included the Siege of La'Victoria, the Battle of San Romero, the First and Second Battles of La'Libertad, the Battle of the San Carlos Islands, and the Battle of Denshire. The most important battle of the civil war, however, was the Siege of San Salvador which lasted from 1946 to 1949. The siege resulted in the deaths of both Romero I and Miguel VII, who were succeeded by Romero II and Marcos I, respectively. The Romerists eventually defeated the Miguelists in San Salvador in August 1949 and forced the Miguelists to retreat east. During the retreat, various extermination camps of the De-Catholization were liberated.

Adolfosburg, the Miguelists' capital city, fell to the Romerists on 26 September 1949; Marcos I died on 20 September 1949 during the sinking of the MV Toboshi in the Bay of Adolfosburg by the BIC DA 36, which killed over 10,000 people. The final Miguelist forces commanded by Miguel Salinas Ortega surrendered on 30 September 1949 following their defeat in the Battle of the Zapatista River, ending the civil war in a Romerist victory.

Modern Creeperopolis

On 4 October 1949, the victorious Romerists led by Romero II, Sáenz Heredia, and Minister of Defense Alfonso Cabañeras Moreno dissolved the Catholic Imperial Restoration Council and merged all of the country's right-wing political parties into one entity: the far-right Nationalist Creeperian Catholic Royal Initiative and the Pro-Fatherland Front of Unification (IRCCN y la'FPPU), more commonly known as the Creeperian Initiative; Sáenz Heredia became the leader of the Creeperian Initiative, assuming the position of Secretary of the Initiative. Additionally, all other political parties were banned. The Cortes Generales was established as the country's legislature, composed of the Council of Captain Generals and the Council of Viceroys; although the Romero II and Cabañeras Moreno held significant influence, the legislature held most of the power.

Although the civil war ended, the country still faced various internal conflicts, such as the Partisan Resistance by various Miguelist groups who continued to resist following the fall of the National Council, and the Third Senvarian Insurgency of the Senvarian Liberation Front. The Partisan Resistance was fully crushed by 1957 following the Massacre of the Seven Thousand and the Third Senvarian Insurgency was defeated in 1969 following the capture and execution of Killasumaq II.

In 1978, following the assassination of Deltinian imam Iftikhar al-Mutasim, the Society of Deltinian Brothers (SOHEDEL) and the Holy Army of al-Mutasim (SEM) rebelled against the Creeperian government, declaring independence and the Emirate of Deltino and beginning the Deltinian Insurgency. In 1979, the Creeperian government passed the Declaration of War Against Gangs and Criminality which made affiliation with criminal gangs illegal; the gangs retaliated against the Creeperian government, beginning the Mara War. In 1980, the Militarist Front for National Liberation (FMLN) called for Castillianans to rise up against the Creeperian government, beginning the Castillianan Insurgency. In 1981, the Kapahu Alana Revolutionary Movement (MRKA) and the Juan Horacio Palafox y Mendoza Revolutionary Council (CR–JHPM) rebelled against the Creeperian government, beginning the San Carlos Islands Crisis; the crisis ended in 1995, but the MRKA renewed the conflict in 2003.

Creeperopolis went to war with Salisford in 1961 after Salisfordian First Minister Sandro Neri invaded the country to secure land which he believed was integral Salisfordian land. The conflict lasted until 1978 with the signing of the Rubicon Agreement which returned the countries' relations back to the status quo ante bellum. In an attempt to improve relations between the two countries, they co-founded the Cooperation and Development Coalition (CODECO), an international economic and military alliance, in 1981. CODECO has since grown to include several members, making it one of the most powerful international political bodies.

On 18 June 2003, the Creeperian military deposed Emperor Alfonso VI and the Cortes Generales, as they believed that his government was impeding the military's influence over Creeperian politics. The military established the Romerist Military Junta and installed Alfonso VI's son, Alexander II, as the country's emperor. The junta was composed the the coup's four principle organizers: Augusto Cabañeras Gutiérrez, Edmundo González Robles, Arturo Merino Núñez, and Gerardo Barrios Dueñas. The government then organized a series of purges of former government officials who supported Alfonso VI and his ideology of Alfonsism. An Alfonsist government-in-exile existed from 2003 to 2020, when its leader, Antonio Gisbert Alcabú, was captured by the Creeperian Army during Operation Banana and subsequently executed.[1][2]

Since the 2003 coup, the military has been the dominant force in Creeperian politics, followed by the monarchy and then the Cortes Generales, which had all its power effectively stripped away by the military following the coup and the purges. Creeperopolis is currently one of the most powerful countries in the world and supports various far-right political parties around the world—such as the Salvadoran Initiative (INSAL), the Catholic Labor Front (FdLC), the National Reconstruction Party (GAU), Onward Quebecshire (AQ), the Party for National Integrity (PIN), among others—through the International Patriotic League (LPI).

Geography

Creeperopolis is the largest country in Sur and the world's second largest country, covering a total surface area of 3,188,570 sq mi (8,258,400 km2). The country's tallest point is the Cerro Pérez-Juárez—located in the Salvadoran Range on the border with El Salvador in the department of Santa Ana—at a height of 23,294 ft (7,100 m); its lowest point is the Imperial Depression—located in the department of San Romero—at 133 ft (41 m) below sea level. Creeperopolis is a transcontinental country, controlling territory in both Sur and Ostlandet, as well as claiming land on Tierrasur. Mainland Creeperopolis lies between latitudes 25° and 55°S, and longitudes 8° and 90° W.

On the north, Creeperopolis is bordered by Montcrabe; on the west, it is bordered by El Salvador and Salisford; on the south, it is bordered by Sequoyah; in its center, in enclaves the State of the Church. Its border with Montcrabe is the longest international border in Sur. Creeperopolis has coastlines on the Sea of Castilliano to the west, the Senvarian Sea to the south, and the Southern Ocean and Bay of Salvador to the east.

Mountains

The majority of Creeperopolis is composed of plains, woodlands, forests, and jungles, but the country also has various mountain ranges. The country's mountain ranges have been formed either through volcanic activity of tectonic activity. The Atlántidan Range, the San Luísian Range, and the Islan Rise were formed by volcanic activity approximately 4 to 14 million years ago, with the Atlántidan Range being the longest and tallest volcanic mountain range in the world.

Meanwhile, Creeperopolis' other mountain ranges—the Salvadoran Range, the Creeperian Range, the Santa Anan Range, and the Castillianan Rise—were formed by tectonic activity. The Creeperian Range and the Castillianan Rise were formed as a result of the Creeperian Plate colliding into the Southern Ecrosian Plate; the Santa Anan Range was formed by the collision of the Creeperian Plate and the Santa Anan Plate; the Salvadoran Range was formed by the collision of the Santa Anan Plate and the Salvadoran Plate in the south, while in the north, by the Creeperian Plate and Salvadoran Plates colliding. The mountains in the Salvadoran Range are among the tallest in Creeperopolis, as well as the tallest in the world, with the Cerro Pérez-Juárez being the tallest point in Sur on the Creeperian–Salvadoran border.

Rivers, lakes, and islands

Creeperopolis has over 1,000 rivers located across the country, and rivers have historically been an important aspect of its economy, infrastructure, and religion. The historically most important river was the San Romero River, also known as the Xichútepa River, where the proto-Creeperian civilization, Creeperian Confederation, and Kingdom of Creeperia developed. The country's longest river system is the Castilliano–Santa Ana system; originating in the Santa Anan range, the Santa Ana River flows into Lake Castilliano, which then flows to form the Castilliano River, draining into the Sea of Castilliano. The second longest river system, the San Miguel–Asambio–Zapatista system, also provides significant marine traffic for both passenger and cargo services.