Kingdom of Monsilva

Kingdom of Monsilva | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anthem: 山國龍之歌 Shānguó Lóng zhī Gē "Song of the Monsilvan Dragon" | |||||||||||

Location of Kingdom of Monsilva (dark green) in Terraconserva (grey) | |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Amking | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Monsilvan | ||||||||||

| Religion | Folk, Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Monsilvan | ||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1830–1898 | Song | ||||||||||

• 1898–1943 | Qing | ||||||||||

• 1943–1978 | Wang | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1830–1845 (first) | Chai Lin | ||||||||||

• 1962–1978 (last) | Shao Yaoting | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Royal Parliament | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-republican period | ||||||||||

• Established | 1830 | ||||||||||

| 1909–1913 | |||||||||||

| 1928–1933 | |||||||||||

| 1962 | |||||||||||

| 1963–1978 | |||||||||||

| 1972–1978 | |||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1978 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1850 | 10,000,000 | ||||||||||

• 1977 | 36,500,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Monsilvan yupian (¥ or 玉) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Kingdom of Monsilva (Monsilvan: 山華王國; pinyin: Shānhuá Wángguó) was Monsilva between 1830 and 1978. The kingdom emerged from the Kingdom of Great Shan at the end of the Monsilvan Civil War in 1830. The kingdom was founded by Chai Lin, a general who had lead the Liberate Monsilva Movement to victory in the civil war. Chai was also the first Monsilvan prime minister, serving from the establishment of the nation in 1830 until his resignation at the 1845 general election. The kingdom encompassed all of modern-day Monsilva excluding Shaoyu.

The Kingdom was the result of the abolition of absolute monarchy in Monsilva. Although the monarchy was retained, it was lead by the House of Yan with the first emperor being the Song Emperor who was the nephew of the Xuantong Emperor, who was the last emperor of the Great Shan, and the son of Yan Bai who had been a founding member of the Liberate Monsilva Movement and would have been Emperor had he not been killed during the Civil War. The monarch retained powers as Head of State, however the prime minister was now the Head of Government and all laws and decisions had to go through the parliament before being introduced or acted upon.

In the 19th century, Monsilva saw a period of peace and prosperity as its economy gradually grew as trade with neighboring nations and across the Kivu Ocean began increasing. Although the nation was economically stable, it was not stable politically. Frequent political tension between the two main political parties, the People's Culture Party and the Leaders of Parliament Party, caused immense corruption and blackmail. In 1909, the Monsilvan political reform movement began as a series of protests orchestrated across the country against the strict voting laws and electoral manipulation. These protests, after dying down breifly between 1910 and 1913, flared up again after the first 1913 general election, when prime minister Zhong Wei won a second term. In September of 1913, Zhong called a snap-election after being threatened by banishment from office by Emperor Qing. This was Monsilva's first election where the suffrage included all men above the age of 18. In the election, the National Party won for the first time. The NP lead Monsilva for 40 years and in this period Monsilva saw a large growth in economy, political stability and population. It also saw a big step forward in human rights such as universal healthcare, free primary education and women's voting rights.

After the death of the Qing Emperor in October 1943, the Wang Emperor, his nephew, became the next emperor of Monsilva. Wang was well known for being extremely generous with his money and his approval of absolute monarchy. Wang used his power to influence and blackmail many National Party politicians into stepping down in the period from 1947 to 1953 so that the Leaders of Parliament Party could return to power as they were in full support of the new emperor, while the National Party was pushing for a republic. In 1953, the LPP won, lead by Liang Huiqing. Liang was assassinated in May 1962, during his second term. Succeeding him was Shao Yaoting, who initiated martial law in 1963.

During the martial law period from 1963 to the kingdom's end in 1978, Monsilva went from a democratic constitutional monarchy to a dominant-party state lead by an authoritarian military lead regime supported by the monarch. By the 1968 general election, Shao Yaoting's party was winning over 80% of seats in the Legislative Assembly with election fraud being very blatant. Any opposition against Shao's regime would result in being arrested by the extensive military police force that was loyal to him. Around 1965 and 1966, protests began occurring across the country, but were often supressed quickly by the military police. However, the protests began becoming more active and violent over the following years, leading to events such as the Jingtianmen Square massacre. This initiated the creation of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army as a direct opposer to Shao's regime. In the mid 1970s, the Revolutionary Army began orchestrating mass riots in cities across the country, and in 1978 began giving weapons to rioters. It is theorised that some neighboring countries that were against Shao's regime, such as Baltanla, provided supplies and possibly even weapons to the revolutionaries during the riots. In October 1978, the MRA arrested the entire Monsilvan government including the Wang Emperor. Then, on the 25 December 1978, Xu Zhou-da, leader of the MRA, established the Monsilvan Republic, ending the Kingdom of Monsilva.

Contents

History

Background

The Kingdom of Monsilva was established by the Liberate Monsilva Movement which had fought against the government of the Kingdom of Great Shan which had ruled over Monsilva from 1730 after it gained independence from the Empire of Baltanla until 1830 at the end of the Monsilvan Civil War. The Great Shan was an absolute monarchy, with the emperor being advised by the unelected deliberative council. Eventually this system and the mistreatment of the government against the working classes lead to the beginning of the Civil War in 1824 which started with the Liberate Monsilva Movement, lead by Chai Lin and Yan Bai declared northern Monsilva (modern states of Luhai, Leibo and northern Meixian) as an independent state known as 'Monsilva', a name that had been given to the country by many travellers and nations across the Kivu Ocean.

The war ended in 1830 with the occupation of Amking, where the government was located, and Sanzhong, where the emperor was located, by the LMM and the execution of the Xuantong Emperor and Cheng Peng, Head of the Deliberative Council at the time. On the 26 August 1830, Chai Lin and Yan Bai's son, the Song Emperor who was only 10 years old, officially declared the Kingdom of Monsilva as the successor to the Great Shan. Chai Lin became Monsilva's first prime minister.

19th century history (1830–1900)

Chai Lin, after establishing the Kingdom of Monsilva, served as prime minister for 14 years from 1830 until 1845, when he resigned at the age of 61 just before the 1845 general election after suffering from a heart attack. During his premiership, Monsilva saw a large reconstruction effort as people began rebuilding the country after the civil war which had devastated many of Monsilva's towns and cities. Chai Lin was extremely successful in Monsilva's first democratic elections, often winning over 60% of seats for the People's Culture Party in the Royal Parliament.

In the 1855 general election, another party, known as the Leaders of Parliament Party, won. This was the first time the People's Culture Party had not won an election. The LPP, a conservative and nationalist party, was lead by Cheng Li, who became Monsilva's 3rd Prime Minister and the first not from the PC Party. However Cheng Li's success was short lived, as his premiership was highly criticized for its failure to continue the reconstruction efforts at a desirable rate and its hiking of taxes. This lead to Chen resigning in May 1857 and a snap election being called, in which the PC Party returned to premiership under Deng Yahui.

During the premierships of Deng Yahui and Qin Zian, Monsilva began developing its international relations, particularly with neighboring Baltanla as well as countries across the Kivu Ocean. This helped increase Monsilva's exports and is the start towards the country's economic transition from being autarkic to export-oriented. When the LPP returned to power in 1875 under the much more successful Gao Aiguo, he maintained Monsilva's trade relations and began focusing on developing Monsilva's industrialization. Although more successful, Gao was still fairly unpopular amongst the poorer citizens of Monsilva. This unpopularity lead to the prime minister facing two assassination attempts, the second, in March 1882, being successful. Gao was followed by Wu Zhong, who was at first was not much more popular and, although winning, failed to gain a majority in the Royal Parliament in 1885. Wu was responsible for massively decreasing unemployment in the late 1880s and early 1890s, which gained him more popularity amongst poorer citizens. However, after a number of conspiracies began circulating about Wu, his popularity declined and he lost the 1895 election to Lo Zhou, who became Monsilva's first prime minister in the 20th century.

Early 20th century (1900–1928)

The early 20th century saw significant developments to Monsilva's democracy. Up until 1913, every election in Monsilva had had very little suffrage, with voters having to be males with tertiary education and no criminal history or history of any type of mental health issues or learning disabilities, including minor disabilities dyslexia (known as 'word blindness' at the time). This limited suffrage lead to large amounts of proxy votes coming from individuals in poorer families who had managed to gain scholarships at universities and had become the only member in the family qualified to vote. Initially this problem had been ignored as the number of proxy votes had been insignificant, however with the increased numbers of scholarships being handed out at universities during the 1890s and 1900s, they had become a much larger problem. In December 1902, Lo Zhou died from pneumonia whilst still serving his third term. This lead to An Tian, his deputy, to become prime minister. However, An Tian had sever social anxiet disorder (known as 'social-phobia' at the time), and almost never came out of his office. This lead to an easy victory for Zhong Wei of the LPP who defeated An in a landslide in the 1908 general election.

Zhong Wei was the first prime minister to attempt to crackdown on the proxy vote problem. Zhong attempted to end proxy voting by strict surveillance at polling stations and implementing large fines to people who were discovered to be proxy voting. This lead to a lot of outrage amongst voters and non-voters alike which lead to large scale protests, the largest the country had seen so far. These protests are what lead to the intervention by the Qing Emperor, who although was supposed to politically neutral, was obliged by law to 'act on behalf of the people in times of need'. The Emperor gave Zhong an ultimatum: 'call a fair election, or resign with immediate effect'. This took place only a couple months after the first 1913 general election in May. Zhong called a snap election in September of the same year with all men over the age of 18 being permitted to vote, during the preparation period whereby people could register to vote, over one million formerly ineligible voters registered. The election resulted in the first win of the National Party, lead by Mao Yanlin. The win was a landslide and Mao retained premiership for just under 15 years until he resigned in June 1928 citing health issues.

Mid-20th century (1928–1953)

After Mao Yanlin's resignation, he was succeeded by Su Zian. Su was not as popular as his predecessor and was frequently criticized by women for being extremely sexist, claiming that women should never be permitted to vote as they 'wouldn't know what's best for them'. These comments made by Su and many people in his government lead to the Monsilvan civil rights movement which lasted from more or less the beginning of Su's premiership until his death from liver cancer in April 1933, one month before the general election in May of that year. In that one month between Su's death and the election, the role of prime minister was officially vacant, however Heng Lei who succeeded Su as the leader of the National Party served de-facto as prime minister in that period. Heng also managed to pass a legislation which permitted women to vote in the 1933 election during that month. The short time period lead to only a few women registering, however the number of registrations before the 1938 general election was astronomical.

Due to his legislation, Heng lost a lot of popularity amongst many of the more right-wing supporters of the National Party, and ended up in a minority government which he lead for 5 years until the 1938 election where he won a majority. Heng served as prime minister for 20 years, the longest of any prime minister in Monsilvan history as of 2023. During his premiership he was responsible for Monsilva's incredible economic, political and social developments, including universal healthcare, free primary education and women's suffrage. Monsilva was becoming a strong nation on the world stage and began developing a name for itself across Terraconserva.

In 1943, the Qing Emperor died without a son, which lead to his half-nephew, the Wang Emperor taking power as emperor. Wang was infamous for his liberal spending habits and support for authoritarianism. Some believed that the Wang Emperor was in fact illegitimate as some believed that he was the offspring of an affair between his father, Yan Xin, second son of the Song Emperor, and another woman who was not his wife. This belief was later found to be true after a DNA test done in 1986. The people who had believed Wang was illegitimate claimed that Wu Hui, son of the Song Emperor's only daughter, was the actual heir to the throne. In order to counter these beliefs, Wang claimed to be under a new dynastic family, the House of Wang.

After his accession to the throne, Wang began a secret blackmailing campaign, aiming to return the Leaders of Parliament Party to power as they were obedient to the emperor. In the 1953 general election, after the abrupt disappearances and resignations of many National Party politicians with fabricated reasons, the LPP gained power lead by Liang Huiqing.

Downfall of democracy (1953–1963)

With the LPP in power and Liang Huiqing as prime minister, the Emperor began becoming more and more affiliated with politics. He would frequently promote the LPP, and pro-LPP propaganda would pop up all across Monsilva, with many people believing many lies portrayed on the posters as contrary information was well hidden by the government. These subtle authoritarian changes would continue up to the next election in 1958, where the LPP would win a very large majority. With this majority Liang promised to continue Monsilva on its path to a 'strong country sitting high on the global stage'. During the beginning of Liang's second term in 1960 and 1961, many of Monsilva's authoritarian developments such as the frequent propaganda, disappearance of political opponents, and banning of some civil liberties such as eating on public footpaths, began reversing.

This all stopped in May 1962, when Liang Huiqing was assassinated while he was sitting at his desk in the prime ministerial residence in Amking. This lead to Shao Yaoting, the deputy prime minister and minister for the interior, and former army colonel, taking power. Shao claimed that Liang had been killed by an anti-monarchist member of the Monsilvan Communist Party, which was denied by Jiang Zedong, leader of the MCP. However, the communist party was extremely unpopular at the time due to the large amounts of anti-communist propaganda produced in Monsilva due to its two communist neighbours, so very few people believed Jiang. After the establishment of the republic, and a investigation into the government operations during and just before martial law, it was revealed that Shao Yaoting himself had shot Liang at the request of the Wang Emperor.

Martial law period (1963–1978)

Shao Yaoting was a strong supporter of the monarchy and believed that the royal family were a connection between the common person and heaven. The assassination of Liang Huiqing gave Shao an excuse to implement martial law as a 'precaution against immanent threat to Monsilva'. With martial law, Shao was able to use the military as Monsilva's primary policing force. He was also able to pass legislation without discussing with parliament first, however this ability was unnecessary as he also rigged elections by only allowing certain party's counts to be permitted. This rigging meant that the parliament was full of his supporters anyway.

The 1960s in Monsilva mostly consisted of the transition of Monsilva from democracy to authoritarianism, with many of Monsilva's political and social developments being reversed. Monsilva's economy was also seriously damaged, with many domestic companies being forcefully acquired by the government and then underfunded, and many international companies being exiled from the country. Shao attempted to return Monsilva to the autarky it was in the early 19th century, however the pressure he placed on the agricultural industry lead to many of Monsilva's infrastructure and manufacturing industries to take serious hits economically.

In 1965 and 1966, protests began erupting sporadically across Monsilva against the government. This was after the government began restricting travel in and out of the country, leaving many people unable to interact with their families who live abroad. Initially, these protests would be supressed with ease by the armed military police situated in every major town and city in the country. However as these protests began becoming more frequent, better organized and larger, the military police began having a harder time controlling them.

In the mid 1970s, the protests briefly decreased for reasons likely associated with new anti-protest equipment acquired by the police as well as the introduction of the death sentence for protesting against the government, as well as the introduction of shoot-on-site permission for all military police who believe they are under threat. These laws made it very difficult for people to protest. This lead to the creation of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army, which had the goal of developing a paramilitary to directly oppose the government's military police and overthrow Shao Yaoting and his government. The MRA began its riots in 1976, and began its operation to arrest Shao Yaoting at the beginning of 1978.

The Monsilvan Revolution and the mass protests and riots in 1978 are the most violent periods of Monsilva's martial law period, and likely the most brutal years in Monsilvan history. The most violent and largest of these riots was the Jingtianmen Square riot in Amking, in which several hundred people died, including rioters and police. After this, many people within the MRA began acquiring firearms supplied by mostly unknown sources and using them against the police. In November 1978, the MRA stormed the Monsilvan government building in Amking and the royal complex in Sanzhong at the same time resulting in the arrest of Shao Yaoting and the unrequested, but unpunished, murder of the Wang Emperor. Later, on 25 December, the leader of the MRA, Xu Zhou-da would proclaim the Monsilvan Republic.

Politics

The Kingdom of Monsilva was founded as a constitutional monarchy, which placed the emperor as a ceremonial head of state, while the newly created role of prime minister served as the head of government. This was the first time Monsilva had not been run by an absolute monarchy. The goal of the new nation, set out by the first prime minister, General Chai Lin, who had lead the Liberate Monsilva Movement against the Kingdom of Great Shan which proceeded the nation, was to establish Monsilva as a 'democracy lead by the social morals of Ruism'.

Elections before 1963

The first election in the Kingdom of Monsilva, which was also the country's first election ever, was held in 1835. Suffrage in this election was limited, with only men with tertiary education permitted for registration to vote. This meant that only around 6% of the Monsilvan population could actually vote in elections. It remained this way until the September 1913 general election which was called after the Qing Emperor gave Prime Minister Zhong Wei an ultimatum demanding a fair election during the Monsilvan political reform movement which had lasted since 1909. This election increased suffrage to include all male Monsilvan citizens above the age of 18 without a criminal record. At the time, this was seen as the limit of suffrage, and the most democratic elections could get. This belief was challenged again during the Monsilvan civil rights movement in 1928 to 1933, which, along with many other things, demanded suffrage for women over 18. This was successful after the death of Prime Minister Su Zian, who had been blocking any legislation relating to women's suffrage since he became prime minister in 1928.

From 1933 until 1948, Monsilva's elections were considered some of the fairest in the world, with full suffrage for all citizens above 18 and with a record low in political corruption including low election fraud and minimal blackmailing. This fairness began deteriorating after the accession of the Wang Emperor to the Monsilvan throne after the death of the Qing Emperor. Wang began a blackmail campaign soon after his accession in attempt to return the Leaders of Parliament Party, who were loyal to him unlike the incumbent National Party who wished for a republic, to power. He was successful, and in 1953, enough National Party politicians had resigned so that the LPP won the election.

The only election to take place between 1953 and 1963 was the 1958 general election. This election was considered mostly fair, although corruption was much more prevalent. However, this election also saw the change in policy of Prime Minister Liang Huiqing from supporting pro-monarchy and pro-authoritarian propaganda, into trying to develop Monsilva's democracy and civil rights even further, against the Emperor's wishes. This is what likely lead to the assassination of Liang Huiqing in 1962, which was originally blamed on a member of the Monsilvan Communist Party, but was later discovered to be Liang's successor, Shao Yaoting, himself.

Elections after 1963

The 1963 general election, the first under prime minister Shao Yaoting, and the last election in the Kingdom of Monsilva before the implementation of martial law, was riddled with election fraud, corruption and blackmailing. Fifty-seven candidates for seats across the Royal Parliament were removed just before the election: 12 went missing, 34 resigned, 2 died in 'mysterious circumstances' and 9 were deemed 'to unwell to run for candidacy'. In almost all of these situations, the result of their seat was an uncontested win by the LPP. This lead to the party winning an unrealistically large majority in comparison to public opinion, which was still heavily in favor of the National Party.

In the first election under martial law, the 1968 general election, the LPP was winning over 80% seats, with around 60% being uncontested and another 10% being held by parties which were completely obedient to Shao. The final election before the establishement of the Monsilvan Republic in 1978, was the 1975 general election. This election was heavily boycotted, with many polling stations being filled with rioters, some were burnt down or destroyed by other means, and some were left completely deserted. Although the results produced by the government showed that over 70% of the population voted, and 81% of them voted for the LPP, it is actually believed that only 23% of the eligible population actually voted, and an even smaller margin would have actually voted for the LPP.

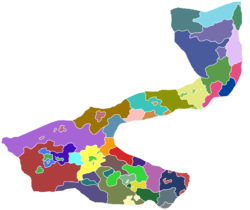

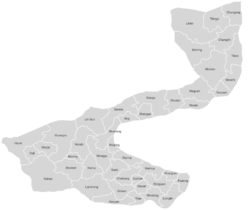

Administrative divisions

At its establishment, the Kingdom of Monsilva was divided into 43 territories which had existed since the independence of the Kingdom of Great Shan in 1730. These territories had become significant in Monsilvan culture, and people from each of these regions were seen as somewhat independent of each other. However, this cultural separation begun deteriorating during the 19th century as people began relocating around the country and immigrants began moving to Monsilva affecting the culture.

The territories were reorganized into counties in 1905 to fit geography more than culture. Their borders were completely different and many had completely different names, however the number only increased by one, from 43 to 44. The counties were only changed again in 1953, when they were replaced by prefectures which were then split into counties, which although having the same name, were one division below the original counties. There were 12 prefectures originally, but the number was decreased to 10 in 1963. These prefectures remained until 1978, after the establishment of the Monsilvan Republic. They were renamed to states in preparation for federalization which took place in 1983. The states were then re-organized for a final time in 1984 leaving Monsilva with the 14 states it currently has today.