1978 Jingtianmen Square protests and massacre

| 1978 Jingtianmen Square protests and massacre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Monsilvan Revolution and the 1978 Monsilvan protests | |||

|

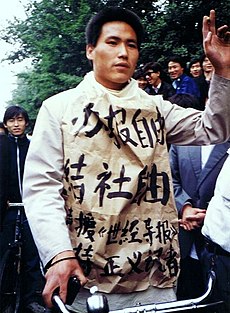

From top to bottom, left to right: Student protesters in the center of the square; Monsilvan tanks lined up in front of a protester; People protesting near the Heroes' Monument; Sun Zhiqiang, a student protester at Jingtianmen; and a banner in support of the June Fourth Student Movement in Luhai Fashion Store | |||

| Date | 15 April – 4 June 1978 (1 month, 2 weeks and 6 days) | ||

| Location | Amking, Kingdom of Monsilva Jingtianmen Square (now known as Memorial Hall Square) | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals | End the regime of Shao Yaoting, abolish the monarchy, restore fair elections, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of association and social equality | ||

| Methods | Hunger strike, sit-in, civil disobedience, occupation, rioting | ||

| Resulted in | Government crackdown

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | See Death toll | ||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Monsilva |

|---|

The 1978 Jingtianmen Square protests and massacre, known in Monsilva as the Fourth of June Incident (Monsilvan: 六四事件; pinyin: liùsì shìjiàn), were student-led demonstrations supported by the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army (MRA) held in Jingtianmen Square, Amking, lasting from 15 April 1978 until the massacre on 4 June of the same year. On the night of 3 June, after several weeks of attempts by the government of the Kingdom of Monsilva to resolve the conflict peacefully, which included negotiations initiated by both sides, the government declared a city emergency and deployed troops to occupy the square, eliminating any demonstrators or rioters that attempted to stop them. This occupation is often referred to as the Jingtianmen Square massacre. The events of the protests, including the massacre, are often considered some of the most important during the Monsilvan Revolution and are the most significant and largest protests that took place during the nationwide demonstrations that had begun in February 1978.

The protests were precipitated by the state execution of Lin Bolin, a 21-year-old student at Central Amking University, who had become one of Monsilva's leading pro-democracy student dissidents during the revolution, on 15 April 1978 amid the backdrop of major inflation, economic decline, military police brutality and deteriorating civil and political rights in Monsilva. The leadership of the Parliamentary Party as the dominant party had been facing serious challenges to its legitimacy over the previous six years, and with the 1975 general election showing that elections were clearly rigged, with an accidental reveal by the government of the number of votes being larger than registered voters in the country, even bringing doubt to the party's most loyal supporters. These challenges had only been made worse by increasing protests and the uncovering of political manipulations being carried out by the government and the monarchy. The common grievances of the people about these issues is what ultimately led to the mass protests of Monsilva, particularly in Jingtianmen Square in the capital. At the height of the protests, around 270 thousand people assembled in the square.

As the protests developed throughout late April and May, the authorities responded with both conciliatory and hard-line tactics. Initially, the government attempted to make peace with the protesters, encouraging them that their efforts were futile. However, as time went on, the negotiations begun moving from peace to bribery and eventually an ultimatum demanding that the protesters leave the square by the end of 3 June or face serious consequences. Around ten thousand people were still in the square by the sunrise on 4 June. Confrontations between the military police and the protesters had already been becoming violent a few weeks before 4 June, however it wasn't until the 1 June that the government made the decision to clear the square completely. At 3am on the 4 June, troops advanced into the central districts of Amking on the city's major roads and engaged in violent clashes with demonstrators attempting to block them. Many people – demonstrators, bystanders, and soldiers – were killed as the soldiers progressed. As the soldiers entered the square, they were met with gunfire and makeshift grenades from members of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army and even some student protest groups.

Kivu, whose relations with the Kingdom of Monsilva had significantly deteriorated during the regime of Shao Yaoting, along with several other foreign countries criticized the Monsilvan government for its handling of the protests, with some governments actively stating their support for the MRA and the student movements. Multiple countries also imposed arms embargoes on the Kingdom of Monsilva, and various media outlets, particularly in liberal democracies in western Ecros and Ostlandet, labelled the crackdown a "massacre". This term was later implemented by the government of the Monsilvan Republic to describe the incident. Due to the event's importance in the establishment of the Monsilvan Republic and its role as one of the most bloody incidents in Monsilvan history, it is one of the most covered and frequently referred to incidents in the country's educational system and politics.

Name

The name used by the Monsilvan government to refer to the event has differed over time since 1978. As the events unfolded and until the arrest of Shao Yaoting in November 1978, it was labelled as a "unruly riot" or a "political turmoil". However, outside Monsilva, particularly in nations like Kivu, who were closely tied to the student movements that took part in the protests, the event was described as a "revolutionary demonstration" and later, as the news of the involvement of the military begun spreading, it was named a "massacre".

After the proclamation of the Monsilvan Republic on 25 December 1978, the event was officially designated by the new government as a "massacre against demonstrators defending their civil rights". However, in Monsilva the more common term for the event has become the "Fourth of June Incident". In Jackian, the terms "Jingtianmen Square massacre" and "Jingtianmen Square protests" are the most often used to describe the series of events. These terms are occasionally used incorrectly to describe the entirety of the 1978 Monsilvan protests, which took place across the country over the span of almost the entire year.

Background

1975 general election incident

In May 1975, the the fourth election under the premiership of Shao Yaoting took place. The previous three elections had been extremely in favor of Shao Yaoting and his party, and some foreign governments had expressed their doubts about their fairness and legitimacy. However, no definitive proof of election tampering or fraud had been found, despite claims from sources in and out of Monsilva. The 1975 election was the first election after 1958 to use a third-party company, Longbu Voting Company, to count all of the votes, as promised by the government the year prior. However, it was well-known that Longbu VC had worked closely with the government before the election, especially during the 1970 and 1968 elections where it had assisted in the counting of votes.

Evidence of election tampering was not discovered during the election until two days after voting and the count had concluded and the announcement of the votes had begun. During the televised announcement of the results, an image was accidentally broadcast showing a tally board with artificial additions of several thousand votes. This was then followed by a broadcaster announcing the number of votes for each candidate, which when added summed to a number larger than the Monsilvan population. It also resulted in an apparent 105% of voters voting for Shao Yaoting and his party. These numbers were later found to not be a broadcasting error and were in fact the numbers produced by Longbu Voting Company.

Despite the vote broadcast being abruptly ceased after the electoral fraud was identified, news of the incident quickly spread around internationally and within Monsilva. The government later announced that the count was an error with the broadcaster and provided a different number which was claimed to be correct, however no evidence that the number was in correct was discovered. An anonymous employee at Longbu VC later revealed recordings and pictures of the vote counting process revealing government officials requesting that the vote be tampered. Some of the pictures also showed valid votes being burned in a large pit outside and behind the company's offices. News of this evidence was quickly discovered in Monsilva, and despite further attempts by the Monsilvan government to censor the information, it had already spread significantly, thanks especially to leaflets distributed by members of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army (MRA).

In the succeeding two months after the election, membership of the MRA doubled. In an interview with Xia Long, a senior member of the MRA from 1977 to 1978 and a member of the Monsilvan Republic's provisional government from 1978 to 1980, he said that he "joined alongside several hundred people from [his] own county who had realised, after the discovery of the government's electoral fraud, that if [they] don't do something about it, [the government] will just keep getting away with it."

Royal involvement in government affairs

Since the death of the Qing Emperor in 1943, his successor, the Wang Emperor, had been increasingly becoming more involved in politics. Under the premiership of Heng Lei, he was frequently reminded by the government not to get involved in political affairs, as it was against one of the first laws written into the country's uncodified constitution at the end of the Monsilvan Civil War. However, after Liang Huiqing won the 1953 general election, the Wang Emperor was permitted to involve himself into politics a lot more. He would frequently commend the Parliamentary Party and documents discovered during the raid of the royal palace in November 1978 showed that the royal family had been funding the party and blackmailing their opposition as early as 1945.

Although the Qing Emperor had been very popular amongst the people, the Wang Emperor did not hold this same reputation. The working class were frequently brought attention to the emperor's generous spending habits by National Party politicians who would remind taxpayers of the percentage of their taxes that went straight to the royal family. However, outrage about the royal family's spending habits got much worse in 1965, after a leak by an anonymous member of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army revealing how much the emperor had spent on purchasing properties across the country for other members of the royal family and for members of the Parliamentary Party. Later in 1976, after a secret investigation done into the government's taxation system, it was revealed that the government had been disguising taxes that went straight to the royal family under the "government budget" heading.

Disenfranchisement and illegitimacy

In 1967, members of the Liang government who continued to serve in Shao's government had originally been led to believe that intellectuals and veteran politicians would play a leading role in guiding Monsilva through traditionalist reforms, but although the country moved towards traditionalism, it did not happen according to the plan set out by Liang Huiqing himself. Despite the government establishing more educational institutions, the state-directed education system did not produce sufficient numbers of graduates to fulfil increased demand in blue-collar jobs in areas of agriculture, light industry, construction and other manual labor professions. On the opposite end of the job market, students specializing in humanities and social sciences experienced extreme difficulty in obtaining work in their respective fields. This was claimed by analysts to not only be caused by an inefficient education system, but also due to increasing favoritism and nepotism, particularly in high-paying jobs.

Facing these issues in the job market, many students sought education and work abroad and those who returned, brought with them a greater vested interest in political issues, particularly republicanism, democratic socialism and progressivism. Groups of students would form small study groups known as "Democracy Barbers" (Monsilvan: 民主理发师; pinyin: Mínzhǔ lǐfǎ shī), on university campuses. These organizations would motivate other students to get involved in politics. Some of them also served as recruitment agencies for the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army.

Simultaneously, the government's nationalist ideology faced illegitimacy as it gradually begun adopting legislations and practices in order to appease Monsilva's multiple communist neighbors, while attempting to push away fellow nationalist nations to appease liberal democracies such as Paleocacher and Kivu, whose governments were already keeping a close eye on Monsilva's internal affairs. Original supporters of the government were discontent with their progress, while those who opposed the government were still unhappy with its extremely conservative policies and increasingly unfair wealth distribution. This left the government with very few allies amongst the general public and a widespread public disillusionment concerning the future of the country.

Nationwide protests and riots

In February 1978, the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army began its principal operation, which would later be discovered to be to arrest the emperor and Shao Yaoting. The paramilitary began its operation by disrupting public transportation and blocking roads with large gatherings of people. In mid-March, it began occupying large areas, preventing police and military personnel from entering by blocking them. However, these areas were mostly residential and did not affect the operations of the government enough for them to resort to anything beyond forming lines to block protesters from making ground. As well as causing disruption, the MRA's goal was to encourage the public to join in the protesters by not only chanting their cause, but also by displaying the inability of the police and armed forces to actually stop them sufficiently.

According to Xu Zhou-da, the leader of the MRA and first president of Monsilva, the army had no intention to cause violence and instead wanted to use political pressure to end the government. However, with the public execution of pro-democracy activist Lin Bolin on 15 April, their policy of pacifism was scrapped and the plan to occupy Jingtianmen Square was created.

Funding and support

During the demonstrations, protesters received a significant amount of support from both domestic and foreign sources. The vast majority of assistance came from the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army, which also organized and took part in the demonstrations within the square. They also were the only source that provided weapons to demonstrators when the Royal Armed Forces begun shooting at protesters on 4 June. Large donations also came from the National Party (who's leader was also leader of the MRA), the Freedom and Democracy Party and the Liberal Party.

Donations also came from Kivu, Jackson, Eleutherios and Entropan. The Kivuian Security and Intelligence Service (SUN) maintained a network of informants among the student activists and the MRA, actively aiding them in forming anti-government movements and providing them with various non-violent equipment. They also organized the smuggling out of several dissident student leaders.

Beginning of the protests

Death of Lin Bolin

On the 15 April 1978, Lin Bolin was publicly executed, after two months of the 21-year-old pro-democracy student dissident being missing. Throughout 1977, Lin had gained a significant reputation, particularly amongst fellow students, for his activism and organized protests outside Central Amking University. When Lin was hanged in front of Nanguan County Prison, thousands of students reacted strongly, and the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army announced it was abolishing its pacifism as they considered Lin's death to be a "declaration of war against democracy". On university campuses across the country, many posters and memorials were created appearing to eulogize Lin, and calling for the honoring of his legacy. Not long after these memorials were set up, posters began moving from Lin towards broader political issues, such as corruption, freedom of speech and freedom of the press. On the evening of the 15 April, students begun marching in large protests from CAU towards Jingtianmen Square, located at the center of Amking.

On the morning of 16 April, the MRA begun distributing leaflets to the leaders of several pro-democracy student groups requesting they take part in an occupation of Jingtianmen Square. Alongside the protests in Amking, hundreds of students in the cities of Luhai, Menchi, Maojie and Wodai also gathered to mourn Lin and protest against the Monsilvan government's corruption and oppression of civil rights. In Luhai, students carried a several meter tall portrait of Lin Bolin along with them, intending to mock the Royal Armed Forces' marches which often featured portraits of Shao Yaoting and the Wang Emperor. The gatherings also featured speakers from various backgrounds who have public orations commorating Lin and discussed social problems faced in Monsilva.

Starting on the 18 April and lasting until the 20 April, two thousand students from Amking Imperial College marched from their campus to the Great Hall of Amking, the home of the Monsilvan parliament and where Shao was located. The students quickly filled the square in front of the Great Hall and were later backed up by several hundred members of the MRA. As its size grew, the gathering gradually evolved into a protest with a draft of pleas for the government:

- Apologize for the execution of Lin Bolin and pardon any crime he was prosecuted for.

- Admit that the government's campaigns against pro-democracy organizations has been wrong.

- Publish information on the income of the royal family and state leaders.

- Allow privately run newspapers and stop press censorship.

- Increase funding on education.

- End all existing restrictions on public protest.

The government never officially responded to the pleas given by the students. On the 20 April, the Monsilvan Imperial Guard arrived to the Great Hall and demanded the students "leave immediately or face consequences". What these consequences were was never discovered, as the vast majority of the students and other protesters left the square by the evening of that day. However, the remaining 150 or so students were either arrested or clashed with the police who used batons. Many of the students who were not arrested brought rumors of police brutality, which quickly spread amongst dissident groups.

Rioting on 22 April

On 22 April, just after 8 pm, serious rioting broke out in Madian, near Amking Dazhen International Airport (ADI). Many rioters committed arson, destroying cars and houses, while others would loot shops near the airport. Around 400 people were arrested for looting. After around seven hours of rioting, some students begun breaching the perimeter fence around ADI Airport despite warnings from protest leaders not to. Around eighty students breached the fence and made it to the closest runway before they were shot and killed by the Royal Police Service for trespassing. After these riots, the commissioner of the Royal Police, Xie Mingyu, requested a meeting with the prime minister. According to reports discovered during the raid on Shao Yaoting's residence, he did in fact meet with Xie, however little is known about what was said at the meeting. MRA leaders believed Xie had suggested working with protesters to try meeting their demands as close as possible to avoid further protesting. Xie went missing two days after the meeting and was replaced on the 25 April.

Media relating to demonstrations on 26 April

Yao Honghui had been a close advisor to prime minister Shao Yaoting since the start of his premiership in 1962, however his relationship with He Changming was difficult as the two often disagreed on matters, particularly relating to protest movements. On 24 April, Shao requested that Yao went to Luhai to manage the protest situation there, while he and He Changming would manage the demonstrations in Amking. He and Shao met with the Mayor of Amking, Zhu Donghai, to guage the situation in central Amking. The officials wanted a quick resolution to the crisis and claimed the protesters were forming a conspiracy to overthrow Monsilva's political system and create a communist government. While Yao focused on negotiations with the demonstrators in Luhai, He Changming endorsed taking a hardline stance against protesters in Amking and suggested taking firm action, and resorting to violence if necessary.

On 26 April, the Shao's Parliamentary Party's official newspaper Ni de Xiaoxi issued a front-page editorial titled "A clear-cut stand against public disturbances is necessary". The language used in the editorial branded the student movements in Amking to be an anti-government revolt. The editorial's harsh wording against the protest movement made it a major sticking point for the remainder of the protests in Amking.

27 April demonstrations

Organized by Amking Federation of Students on 27 April, around 50 thousand to 100 thousand students from all of Amking's universities marched through the streets of the capital towards Jingtianmen Square, adding significant numbers to the existing student protests. The marches were so large, they managed to break through lines set up by police and received widespread public support, in the form of donations to cheers from buildings, as they travelled through the streets. The student leaders, wanting to show their intent for the protests to be patriotic, used messages of anti-corruption and pro-freedom of speech, but no actual attacks towards the royal family or members of the government. Ironically, those who called for an end to the monarchy and Shao Yaoting's government received the most funding and traction, especially thanks to the 26 April editorial on Ni de Xiaoxi.

The success of the march pressured the government into making concessions when meeting with student representatives. On 29 April, around seven student leaders met with Parliament Spokesman Qin An to discuss a wide range of issues, including the editorial, the Amking Dazhen International Airport incident and freedom of the press. The talks gave negligible results, with Qin An claiming that since no leaders from any of the major student movements, such as the Amking Federation of Students or the Return Our Democracy Foundation attended, there was not a good enough reason for the government to take such drastic concessions.

The government's tone became much more conciliatory when Yao Honghui returned from Luhai on 30 April and reasserted his authority. In Yao's opinion, He Changming's hardline approach was not working, and concessions yet to be given by the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army and the major student groups were the only alternative. Yao asked that the press be allowed to positively report the movement, and he gave two student-sympathetic speeches on 1-2 May. In his speeches, Yao said that the student's had justified concerns about corruption and their intentions were good. However, he also insisted that the decision to occupy Jingtianmen Square was a step too far and that they should retreat and instead focus on discussing agreements with the government. Yao's speeches were sufficient reason for the Amking Federation of Students to retreat from the square, and Tao Zihao, leader of the AFS, begun discussions with Yao and other senior government members for concessions. However, for some, including the Central Amking University movement, Yao's speech was not good enough and around ten thousand people remained in the square. The MRA also disagreed with Yao's speeches and claimed that "concessions are not good enough, the only option is for the entire government to resign".

Escalation of the protests

Polarization within the government

With the return of Yao Honghui on 30 April, the government was divided on how to respond to the movement. Yao lead the progressive camp, wanting to negotiate with the protesters and find a compromise with their final goal claiming to be to put an end to any future protests, while He Changming lead the conservative camp, which wanted to put an end to the protest by any means possible with out making any concessions. Although initially the progressive camp dominated the government, as Shao Yaoting begun gradually leaning towards the conservative camp, so did large portions of the government. During a meeting of senior government members, Yao and He clashed. He maintained that the need for stability overrides all else, while Yao insisted that the government should show support for increased democracy and transparency which would better relations with the public and internationally. This meeting resulted in many ministers rallying behind He Changming, with Yao losing many of his supporters, including the prime minister. According to records of the meeting, Shao asked Yao to end the protests through negotiations by the 15 May, otherwise he will be removed from government meetings.

In preparations for the dialogues between Yao and student leaders, the student unions elected representatives to a formal delegation. However, there was friction between Union leaders, who were reluctant to let the delegation unilaterally take control of the movement. The MRA eventually agreed, although against negotiations, to accompany the delegates at the request of multiple student organization leaders. Some student leaders distrusted the government's offers of dialogue, dismissing them as a ploy designed to play for time and pacify the student movement. Several senior members of the MRA also held this view and requested delegates only let negotiations last two days.

After two days of negotiations, the students were unhappy with the compromises suggested by Yao and the other government members that attended the dialogues. Student leaders began calling for a return to more confrontational tactics and planned to mobilize students with support from the MRA for a hunger strike which would begin on 13 May. Xu Zhou-da, leader of the MRA, strongly supported the movement and made an emotional appeal the night before the strike began encouraging a significant number of students to join.

Hunger strikes begin

Students began the hunger strike on 13 May, in an attempt to gain widespread sympathy from the population at large. The student leaders believed that the increased sympathy would put more pressure on the government, particularly if they could get sympathy from powerful individuals, such as members of the royal family or members of the Parliamentary Partyy. The hunger strikes were successful in increasing numbers of protesters, with many students and young people travelling from across Amking and from other cities to Jingtianmen Square in order to take part. By the afternoon of 13 May, some 250,000 people had gathered in the square.

On 15 May, the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army began marching its members into the square to defend the student protesters against the encroaching police forces. The marching members would sing the anthem of the MRA, which would later become the National Anthem of Monsilva after the establishment of the Monsilvan Republic.

International attention and increased momentum

The hunger strikes, having lasted five days by 17-18 May, sympathy had not only been aroused within Monsilva, but also internationally. Around a million residents from Amking alone demonstrated in solidarity with the students. On 19 May, several foreign governments, including Kivu and Entropan, expressed their support for the student demonstrators. Several Monsilvan labor unions, political parties and youth leagues encouraged their membership to demonstrate. On 20 May, the Monsilvan Red Cross begun sending personnel to provide medical services to the hunger strikers on the square. Alongside the Red Cross, hundreds of foreign journalists remained in Amking to cover the protests, growing the international spotlight on the movement. Outside of Amking, similar protests begun springing back into action after diminishing in late April. Around 15 Monsilvan cities featured large demonstrations, particularly in Luhai, Menchi, Wodai and Maojie.

As the protests began reaching unprecedented sizes, with the majority of demonstrators being independent of any unions or foundations, there was no clearly articulated position amongst protesters. This made it unclear to the government on what the protesters demands were. The government was still split on who to deal with the movement, and watched its authority gradually erode as the hunder strikers continued with no signs of slowing down. These combined circumstances put immense pressure on the authorities to act.

After failing to reach a compromise with the student leaders, Yao Honghui was removed from government meetings, and He Changming was put in charge of ending the movement. He warned the government that "there is no way to back down now, if we do, the situation will spiral out of control".

Surveillance of protesters

Student leaders were put under close surveillance by the authorities; traffic cameras were used to perform surveillance on the square; and nearby restaurants, and wherever students gathered, were wiretapped. This surveillance led to the identification, capture, and punishment of protest participants. After the massacre, the government did thorough interrogations at work units, institutions, and schools to identify who had been at the protest.

Military action

May

On 23 May, the Monsilvan government mobilized at least 30 divisions towards Jingtianmen Square in order to disperse protesters. Civil airline travel was suspended to all Amking airports during the military operation to allow for the transporting of military units from other parts of the country.

The army's initial entry into Amking's city center was blocked in the suburbs by groups of protesters. They saw no way to advance without running people over, and the authorities ordered troops to temporarily withdraw on the 24 May. All government forces then grouped at bases on the edges of the city. Many protesters believed the withdrawal was a turn of the tide in favor of the demonstrations, however, the retreat and regroup was actually in preperation for a larger mobilization and final assault.

At the same time as the army was regrouping, the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army was struggling to keep up with the large number of protests and losing their grip on leadership. On top of this, the square was getting incredibly overcrowded and people were getting unhappy with being squashed and increasing hygiene problems. The MRA began trying to encourage protesters to spread outside of the square, however this became increasingly difficult as roads surrounding the square were already filled with people and vehicles. The MRA also observed the military units remaining in the outskirts of the city and feared, correctly, that a final assault was being planned. This divided the organization into two groups, one which wanted to get people out of the square to avoid a massacre, and the other to fight back against the army to show strength.

1 June

On 1 June, He Changming issued a report titled "The True Nature of the Demonstration", which was circulated to every member of the government's intelligence department. The report stated that the demonstrators' leadership had organized the demonstrations to create fear amongst the people and force the government into becoming a socialist state. It also maintained that they had formed connections with criminal elements and received funding from foreign and domestic sources. The report concluded with a recommendation for the government to "take swift and decisive measures immediately to suppress the counterrevolutionary turmoil".

Following the report, the government of Kivu contacted multiple leaders of the student movement reassuring them that "Kivu would, if necessary, provide asylum for students or help them continue their studies in Kivu."

2–3 June

On 2 June, the government made a final decision to clear the square using any means necessary. Outrage amongst the public increased as newspapers published articles that called for the demonstrators to leave Jingtianmen Square and end the movement or face unavoidable consequences. Despite the release of these articles, relatively few protesters left the square. But after weeks of occupying the square, students were getting hungry and tired and internal rifts began forming between the moderate and hardline student groups.

On 3 June, the senior-most members of the government met with the leaders of the troops on the outskirts of Amking. They agreed that the square needed to be cleared as peacefully as possible; but if protesters did not cooperate, the troops would be full authorized to use any force necessary to complete the job. That night, the troops were positioned in several key areas in the city, ready to move into the square. Witnessing a sudden movement in the troops, the leadership of the MRA begun mobilizing their own members to construct barricades around the square to make it as difficult as possible for the troops to progress. Weapons were also anonymously brought into the square, although unconfirmed, multiple sources claim they came from Taidu members.

3–4 June

In the late evening on 3 June, the government issued an emergency announcement to all Amking citizens urging them to "stay away from the square and stay off the streets". These warnings failed to keep as many people inside as the government had intended, especially after a previous similar announcement had been succeeded by very little action, causing many people to believe they were just scare tactics rather than genuine warnings. Meanwhile, the MRA began their own broadcasts encouraging those who remained in the square to arm themselves and assemble at intersections.

Jinhai Avenue

On 3 June, at 8:00 p.m, troops in eastern Amking, began to advance from military office compounds along Jinhai Avenue towards Jingtianmen Square. At 9:30 p.m, the army encountered its first blockade set up by protesters in Zhufengong and the first warning shots of the incident were fired into the air. These first shots failed to disperse the protesters, who began throwing rocks, bricks and bottles at them. At around 10:15 p.m, an officer picked up a megaphone and urged protesters to disperse or stun grenades will be used. After two minutes of waiting, the protesters failed to move as requested, and the army threw the stun grenades towards them. When these measures failed, the officer ordered the troops to aim their weapons at the protesters and giving them a final chance to disperse.

Soldiers attack protesters

At around 10:45 p.m, still being hit by rocks and bricks thrown by protesters, the army opened fire. APCs rammed through the makeshift barricades the protesters had set up at the intersection, killing civilians in the process. The crowds that had formed near the protesters were shocked by the army's use of live ammunition and immediately retreated into buildings or back towards river.

The advance of the army was halted a second time at another blockade at the Dimu Bridge, just a couple kilometers from the west of the square. After protesters repelled an attempt by an anti-riot brigad attempting to storm the bridge. The regular troops advanced on the crowd and turned their weapons on them. The soldiers were indiscriminate in their firing and shot at any people who got in the way of the progressing army, including both protesters and bystanders. As the army advanced and news of the fatalities began to spread to the people on the square, the MRA began mobilizing its own paramilitary to defend protesters on the square.

Protestors attack soldiers

After hearing of the fatalities along Jinhai Avenue, Xu Zhou-da and other senior members of the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army decided that they would fight back against the army with weapons of their own. Although only a few members had firearms, many protesters had other weapons, such as rocks, poles and molotov cocktails. As troops began advancing on the square, protesters threw these weapons at them, resulting in several vehicles being set on fire and plenty of troops being shot by MRA members stationed around the square, on top of buildings and in intersections.

As troop numbers began dwindling, protesters would run up to burning vehicles, pulling personnel out and beating them with batons, leaving many to die on the road. Many journalists reported after the incident on 5 June, that "despite their positive cause", hundreds of the protesters had "fallen to crowd mentality" and "committed worse atrocities than perhaps even their enemies".

Clearing the square

The initial failure of troops to fully clear the square lead to the introduction of several other units, including tanks. On the morning of 4 June, the first tank entered Jingtianmen Square. It was attacked by molotov cocktails and briefly immobilized by a traffic divider. As the tank moved further in, it was then set on fire using blanket doused in petroleum. According to several witnesses, the driver of the tank was pulled out as it was on fire and protected by some student protesters from other demonstrators who had more violent intentions.

After this incident, more tanks were mobilized into the square and members of the student leadership began encouraging people to leave the square. One member of the MRA used a loudspeaker to tell protesters that "you can't keep fighting if you're obliterated by a tank". After the announcement, most people in the square began to leave, and by 2:00 am, there were only a few thousand demonstrators in the square. North of the square, a dozen students and citizens attempted to torch army trucks with cans of petrol but were arrested.

By 3:00 am, the vast majority of the MRA members and student protesters had evacuated the square. At 3:45 am, ambulances arrived at the northeast corner of the square to assist troops and protesters who had been severly injured during the fighting. Most protesters had been able to escape the square before the arrival of the final army unit. However, those that had not were paraded down Jinhai Avenue by a line of tanks. Around five hundred protesters were arrested in this parade.

Later in the morning, thousands of civilians tried to re-enter the square from the northeast on East Jinhai Avenue, which was blocked by infantry ranks. Many in the crowd were parents of the demonstrators who had been in the square. As the crowd approached the troops, an officer sounded a warning, and the troops opened fire. The crowd scurried back down the avenue, in view of journalists. Dozens of civilians were shot in the back as they fled. Later, the crowds surged back toward the troops, who opened fire again. The people then fled in panic. An arriving ambulance was also caught in the gunfire. The crowd tried several more times but could not enter the square, which remained closed to the public for two weeks.

5 June and the Tank Man

On June 5, having secured the square, the military began to reassert control over thoroughfares through the city, especially Jinhai Avenue. A column of tanks left the square and heading east on Jinhai Avenue and came upon a lone protester standing in the middle of the avenue. The brief standoff between the man and the tanks was captured by media atop a nearby hotel, where they had been told to stay. After returning to his position in front of the tanks, the man was pulled aside by a group of people. There have been several witness accounts of the situation, almost all of these have different opinions on who the group of people were.

The fate of the 'Tank Man' is unknown, even after the establishment of the Monsilvan Republic later that year.

A stopped convoy of 37 APCs on Jinhai Boulevard were forced to abandon their vehicles after becoming stuck among an assortment of burned-out buses and military vehicles. In addition to occasional incidents of soldiers opening fire on civilians in Amking, foreign news outlets reported clashes between units of the Royal Army. By and large, the government regained control in the week following the square's military seizure. Despite this, many protest leaders were not arrested, and had either been successfully hidden by the MRA, or had escaped via Operation Greenbird, created by the Kivuian Security and Intelligence Agency.

Death toll

The number of deaths and the extent of bloodshed in the square itself is largely unknown. The government actively suppressed discussion of casualty figures immediately after the events, and even after raids on government buildings in November 1978 during the eventual collapse of Shao Yaoting's government, no concrete information on the death toll of both soldiers or civilians was recorded.

Estimates

On the morning of 4 June, many estimates of deaths were reported by foreign media. Central Amking University leaflets circulated on campus suggested a death toll of between two and three thousand. Several other sources, including both domestically and internationally, recorded deaths lying between one thousand to five thousand people. The Monsilvan Revolutionary Army claims around three thousand people were killed, including both civilians and soldiers, however in 1981, Xu Zhou-da claimed that this number was an estimate.

Immediate aftermath

Arrests, punishments, and evacuations

On 13 June 1978, the Monsilvan government released an order for the arrest of 11 students they identified as the protest leaders. All 11 of these student leaders were members of the Amking Federation of Students. None of these students were ever arrested. Only six of them resurfaced after the establishment of the Monsilvan Republic, as they had been hidden by the Monsilvan Revolutionary Army, while the other four likely escaped the country through Kivu's Operation Greenbird.

The most-wanted list of students were broadcast on television frequently over the following months. Photographs and biographies were also distributed of the student leaders. The remaining student leaders who were not on the wanted list, either escaped prosecution or were apprehended and incarcerated. Many of those who escaped returned to Monsilva in 1979, however some decided to remain the countries they escaped to.