Sumeria

| File:Samirian cities.png Samirian city-states along the Alaius | |

| Geographical range | Alaia, Caelean Coast |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic, Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 4500 – c. 2000 BC |

| Followed by | Akadia |

| The Ancient Caelean Coast |

|---|

|

| Regions and states |

| Archaeological periods |

| Languages |

| Literature |

| Mythology |

Samiria is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of the Ancient Caelean Coast and Alaia, emerging during the Neolithic and Bronze Age in the fifth millennium BC. It is also one of the oldest civilizations in the world. Living along the valley of the Alaius and its tributaries, Samirian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, which enabled them to form urban settlements. Samirian cuneiform to inscribe the Samirian language dates back before 3000 BC.

Contents

Name

Samiria comes from Samirian for 'the black-headed people' (𒊕 𒈪, saĝ-gíg, 'head' + 'black', or 𒊕 𒈪 𒂵, saĝ-gíg-ga, 'head' + 'black' + 'carry'). The Akadians called Samirians ṣalmat-qaqqadi, meaning 'black-headed people', in the Akadian language.

Samirians more often referred to themselves as Kenger, meaning 'Country of the noble lords' (𒆠𒂗𒄀, 'country' + 'lords' + 'noble').

City-states

In the late 4th millennium BC, Samiria was divided into many independent city-states. Each was centered around a temple dedicated to a particular patron god or goddess and ruled by a priestly governor (ensi) or king (lugal).

Pre-dynastic city-states:

Dynastic city-states:

History

Origins

Samiria was first settled between c. 5500 and 4000 BC by a people who spoke the Samirian language.

Samirian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Furzat period. Samirian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic period in c. 23rd century BC.

Furzat period

The Furzat period (c. 5500-4100 BC) is marked by fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Alaia and the Caelean Coast. The first settlement near the Alaius was established at Iridu in c. 6500 BC by farmers who first pioneered irrigation agriculture. It is unknown whether or not these were the actual Samirians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. Many historians estimate the Samirians succeeded the original settlers c. 5500 BC or later.

Uruk period

The transition from the Furzat period to the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC) is marked by a shift from painted pottery produced on a slow wheel to unpainted pottery mass-produced on fast wheels.

The volume of goods transported along the canals and rivers of the Alaius brought the rise of many large, temple-centered cities with populations over 10,000. Samirian cities began to use slave labor captured from neighboring rural areas.

Uruk culture spread via Samirian traders and colonists to surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own economies and cultures. Samiria could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.

Samirian cities were theocratic and headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women. The later Samirian pantheon was likely modeled upon this political structure. There is little evidence of organized warfare or professional soldiers during the Uruk period, and towns were generally unwalled. During this period Samiria became the most urbanized place in the world, surpassing 50,000 inhabitants.

The ancient Samirian king list includes the early dynasties of several cities from this period. The first set of names on the list is of kings said to have reigned before a major flood occurred. These early names may be fictional, and include some legendary and mythological figures, such as Alulim and Dumizid.

Early Dynastic period

The dynastic period (c. 2900-2350 BC) is marked by a shift from the temple establishment headed by an ensi and council of elders to leadership by a more secular Lugal (Lu = man, Gal = great). It includes legendary patriarchal figures such as Dumuzid, Lugalbanda and Bilgamesh. The center of Samirian culture remained at the Alaius, even though rulers soon began expanding into neighboring areas and neighboring Semitic groups adopted Samirian culture.

The earliest Samirian king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Mebarasi of Kish, whose name is also mentioned in the Bilgamesh epic, leading to the suggestion that Bilgamesh himself might have been a historical king of Uruk. As the Epic shows, this period was associated with increased war. Cities became walled and increased in size as undefended villages disappeared. Bilgamesh is credited with having built the walls of Uruk.

Akadian Empire

- Main article: Akadia

The rise of the Akadian Empire in the 24th century BC made the Semitic Akadian language more common in the civilizations near the Alaius, though Samirian remained the primary written language until 1800 BC. Samirian was increasingly becoming a literary language only known by scholars and scribes.

Neo-Samirian period

The 3rd dynasty of Ur (c. 2112-2004 BC), whose power extended as far as Ashoria, was the last great Samirian renaissance. However, the region was becoming more Semitic than Samirian, with the increase of the Akadian-speaking people and the influx of Murtans.

Fall

Samirian land was compromised by poor land irrigation which led to the build up of salts in the soil. This severely reduced agricultural yield and greatly upset the balance of power within the region, weakening the areas where Samirian was spoken and strengthening those where Akadian was spoken. Henceforth, Samirian would remain only a literary and liturgical language.

Following an Elamite invasion and sack of Ur (c. 2028–2004 BC), Samiria came under Murtan rule until they were later conquered by Ashoria in X BC.

Culture

Social and family life

In the early Samirian period, primitive pictograms suggest:

- Pottery with a variety of forms of vases, bowls, dishes, etc; jars for honey, butter, oil and wine (probably made from dates).

- Feathered head-dresses were worn.

- There were fire-places and fire-altars.

- Knives, drills, wedges, and saws were crafted; spears, bows, arrows, and daggers (but not swords) were used in war.

- Necklaces or collars made of gold were worn.

- Clay tablets were used for writing.

- Time was tracked in lunar months.

There is considerable evidence of Samirian music. Lyres and flutes were played, with the Lyres of Ur being the best example.

Inscriptions describing the reforms of king Urukagina of Lagash (c. 2350 BC) say that he abolished polyandry, ordering that a woman who took multiple husbands be stoned with rocks upon which her crime had been written.

Samirian culture was male-dominated and stratified. The Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest codification of Samirian laws discovered, reveals the societal structure in Samirian law. Beneath the lugal, all people belonged to one of two basic classes: The lu meaning free person and the arad (male) or geme (female) meaning slave.

Marriages were usually arranged by parents; engagements were done through contracts written on tablets. These marriages became legal as soon as the groom delivered a gift to his bride's father. Samirian proverbs describe the ideal, happy marriage as one in which the husband boasts that his wife has borne him eight sons and is still eager to have sex.

Samirians generally discouraged premarital sex. They, as well as the later Akadians, had no concept of virginity. Samirians had no knowledge of the existence of the hymen. Samirians believed that masturbation enhanced sexual potency for both men and women. They did not consider anal sex taboo either. Entu priestesses were forbidden from having children. Prostitution and sacred prostitution also likely existed.

Language and writing

The most important archaeological discoveries in Samiria are clay tablets written in cuneiform script. Samirian writing is considered a milestone in the development of humanity's ability to create historical records and literature, in the form of epic poems, stories, prayers, and laws.

Triangular reeds were used to write on moist clay. Hundreds of thousands of texts in Samirian have survived, including letters, receipts, lexicons, laws, hymns, prayers, stories, and other records. Full libraries of tablets have been found. Inscriptions on other objects, like statues or bricks, were also common.

The Epic of Bilgamesh was a long cuneiform poem written in Samirian and is one of the most studied pieces of Samirian and ancient literature. It tells the story of a king from the early Dynastic period named Bilgamesh. It was written on several clay tablets and is thought to be the earliest known surviving piece of fictional literature.

The Samirian language is an agglutinative language isolate. Understanding Samirian texts today can be difficult because of a lack of information on Samirian grammar.

During the 3rd millennium BC, a cultural symbiosis developed between the Samirians and the Akadians, which included widespread bilingualism. The mutual influences between Samirian and Akadian are apparent in all areas including word borrowing on a massive scale, and syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.

Akadian gradually replaced Samirian as a spoken language somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC, but Samirian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, and literary language in Akadia and then Ashoria until around 500 BC.

Religion

Samirian religion was founded on cosmogenic myths. First, Namma, the primeval waters, gave birth to An (the sky) and Ki (the earth), who mated together and produced a son named Enlil. Enlil claimed the earth as his domain. Humans were believed to have been created by Enki, the son of Nammu and An. The gods were said to have created human beings from clay for the purpose of serving them. This involves reconciliation between opposites, regarded as a joining of male and female divine beings. It mirrors the way muddy islands emerge from the joining of fresh and salt water at the mouth of the Alaius, where the river deposits its load of silt.

This pattern continued to influence regional Alaian myths. Thus, in the later Akadian creation myth, creation was seen as the union of fresh and salt water, between male Abzu and female Tiamat.

Dieties

Samirians believed in anthropomorphic polytheism. There was no single pantheon; each city-state had its own patrons, temples, and priest-kings. Nonetheless, these were not exclusive; the gods of one city were often acknowledged elsewhere. Samirian speakers were among the earliest people to record their beliefs in writing.

Samirians worshiped:

- An as the god equivalent to heaven; the word an in Samirian means sky and his consort Ki means earth.

- Enki in the east at the temple in Iridu. Enki was the god of beneficence and of wisdom, ruler of freshwater beneath the earth, and a healer and friend to humanity who was thought to have given humans the arts and sciences. The first law book was considered his creation.

- Enlil was the god of storms, wind, and rain. He was the patron god of Nibur.

- Inanna was the goddess of love, beauty, sexuality, prostitution, and war; Venus was deified as Inanna at the temple at Uruk.

- Utu the son god at Larsam in the east and Zimbir in the west,

- Sin the moon god at Ur.

These deities formed a core pantheon; there were additionally hundreds of minor ones.

Cosmology

Samirians believed that the universe consisted of a flat disk enclosed by a dome. The afterlife was a descent into a dark, dusty netherworld to spend eternity as a ghost.

The universe was divided into four quarters:

- To the north were the hill-dwelling Murtans, ancient Semitic-speaking peoples living as pastoral nomads tending herds of sheep and goats.

- To the south were the tent-dwelling Amorites, who were periodically raided for slaves and raw materials.

- To the west were the Elamites, a rival people with whom the Samirians were frequently at war.

- To the east was the Caelean sea.

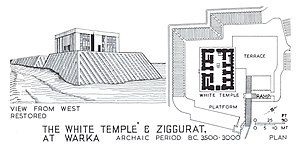

Temples

Ziggurats (Samirian temples) each had an individual name and consisted of a forecourt, with a central pond for purification. The temple had a large hall with aisles along either side. A podium and table for sacrifices would be at one end. Samirians began to build temples on multi-layered squares to form a series of rising terraces, giving rise to the Ziggurat style.

Funerary practices

It was believed when people died, they would be sent to the gloomy world of Ereshkigal, which was guarded by gates with various monsters to prevent people from entering or leaving. The dead were buried in graveyards outside the city walls. Earth mounds covered the corpses, along with offerings to the monsters. Evidence of human sacrifice was found in the death pits at the Ur royal cemetery in which royalty was accompanied in death by servants.

Agriculture and hunting

The Samirians adopted an agricultural lifestyle as early as c. 5000–4500 BC. The region used a number of agricultural techniques, including organized irrigation, intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping ploughs, and bureaucratically managed specialized labour forces. Pictograms suggest the Samirians had domesticated sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. They used oxen as beasts of burden and donkeys as primary transport animals.

The Samirians grew barley, chickpeas, lentils, wheat, dates, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks and mustard. They caught fish and hunted fowl and gazelle. The Samirians were one of the first known societies to drink beer. Cereals were plentiful, and they brewed multiple kinds of beet consisting of wheat and barley.

Samirian agriculture depended heavily on irrigation. The irrigation was accomplished using canals, channels, reservoirs, and other techniques. The frequent violent floods of the Alaius meant that canals required frequent repair and continuous removal of silt. By the Ur period, farmers had switched from wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley as their principal crop due to increased soil salinity.

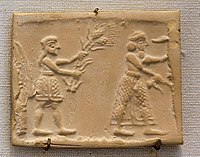

Art

Samirian artifacts show great detail and ornamentation, incorporating stones such as lapis lazuli, marble, and diorite and metals like gold. Stone was often reserved for sculptures. The most widespread material in Samiria was clay, which explains the abundance of clay Samirian objects. Some of the most famous masterpieces are the Lyres of Ur, which are considered to be the world's oldest surviving stringed instruments.

Architecture

Samirian structures were made of mudbrick. Mud-brick buildings eventually deteriorate, so they were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This constant rebuilding gradually raised the level of cities. Houses had a tower-like appearance. City gates were large and double doored. The most impressive and famous of Samirian buildings are the ziggurats. The Samirians also developed the arch, which allowed build domes by constructing and linking several arches.

Economy

Discoveries of obsidian from far-away locations in Malgax and lapis lazuli near the Vantharus and Theumus rivers, beads from Alaqa, and several seals inscribed with Alaqan hieroglyphs suggest a wide-ranging network of ancient trade centered on the Caelean Coast. The Epic of Bilgamesh refers to trade with far away lands for goods, such as wood, that were scarce in Samiria.

The Samirians used slaves captured from neighborring peoples, although they were not a major part of the economy. Slave women worked as weavers and millers.

Samirian potters decorated pots with cedar oil paints. Samirian masons and jewelers used alabaster, ivory, iron, gold, silver, carnelian, and lapis lazuli.

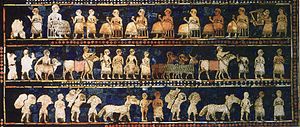

Military

Samirian military technology and techniques was quite developed because Samirian city-states were in almost constant wars for 2000 years. The first recorded war was between Lagash and Umma c. 2450 BC depicted on the Stele of the Vultures. It shows the king of Lagash leading an army of mostly of infantry who carried spears and rectangular shields and wore copper helmets. The spearmen are arranged in the phalanx formation, which requires training and discipline, which implies that the Samirians may have made use of professional soldiers.

Samirian militaries used four or two-wheeled carts tied to four onagers and manned by a crew of two. These chariots functioned less effectively in combat than later designs.

Samirian cities were surrounded by defensive walls. The Samirians engaged in siege warfare between their cities.

Technology

Samirian technology included: the wheel, cuneiform script, arithmetic and geometry, irrigation systems, boats, lunisolar calendar, bronze, leather, saws, chisels, hammers, braces, nails, pins, rings, hoes, axes, knives, lancepoints, arrowheads, swords, glue, daggers, waterskins, bags, harnesses, armor, quivers, war chariots, scabbards, boots, sandals, harpoons and beer.