Difference between revisions of "Dáidism"

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

| headquarters = [[Tildøs Voda]], [[Veli]], [[Uryha]], Entropan | | headquarters = [[Tildøs Voda]], [[Veli]], [[Uryha]], Entropan | ||

| separations = | | separations = | ||

| − | | number_of_followers = | + | | number_of_followers = 15-17 million |

| area = Predominant religion in [[Entropan]] (49%), and [[Dáidism by country|exists worldwide]] as minorities. | | area = Predominant religion in [[Entropan]] (49%), and [[Dáidism by country|exists worldwide]] as minorities. | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 13:14, 28 November 2024

| Dáidism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scripture | |

| Theology | |

| Governance | Tildøs Voda |

| Region | Predominant religion in Entropan (49%), and exists worldwide as minorities. |

| Language | Uryha Šebukel Rockr Leintan |

| Headquarters | Tildøs Voda, Veli, Uryha, Entropan |

| Founder | Laalmmái Ertek |

| Origin | 10th century CE Uryha, Entropan |

| Number of followers | 15-17 million |

Dáidism, also known as Dáide, is a monotheistic religion and philosophy that originated in the Uryha country of Entropan around the end of the 11th century CE. Dáidism is classified as a northern and Dharmic religion, alongside Buddhism.

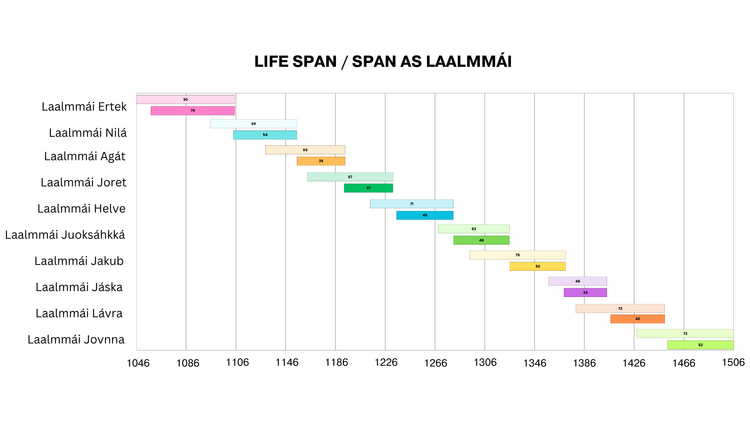

Dáidism developed from the spiritual teachings of Laalmmái Ertek (1046-1105), the faith's first Laalmmái, and the nine Dáide Laalmmái who succeeded him. These ten Laalmmái contributed to the scripture of Dáidism, recorded in the Laalmmái Bihcien (Laalmmái Hoarfrost), the Laalmmái Dihkten (Laalmmái Poetry), and the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš (Laalmmái Law).

The core beliefs and practices of Dáidism, articulated in the Laalmmái Bihcien, include faith in the one true creator and the divinity of all created (Oktet Ipmil), the divine unity and equality of all humankind, engaging in selfless service to others (Addála), rejecting tribalism in favour of a unified human identity (Múhtan), and striving for justice and the benefit and prosperity of all (Oppamáilmmalaš). Doing this, Dáide strive to become co-creators (Ta-dáiddarat) with God, utilising the divinity inherent within to carry out God's morality. Dáidism reject claims that any particular religious tradition has a monopoly on absolute truth. As a consequence, Dáide do not actively proselytise, although voluntary converts are always accepted. Dáide practices are simple, with the belief that complication of religious beliefs leads to self-serving ceremony (Iešbuorrahet).

- One Immortal Being,

- The divinity of the Ten Laalmmái, from Laalmmái Ertek to Laalmmái Ápmot,

- The teachings enshrined in the Laalmmái Bihcien, the Laalmmái Dihkten, and the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš and,

- The universal baptism bequeathed by the ninth Laalmmái, and who does not owe allegiance to any other religion, is Dáide.

Contents

- 1 Terminology

- 2 Philosophy and teaching

- 3 Scripture

- 4 Observances

- 5 History

- 6 Main branches or denominations

- 7 Law

- 8 Prohibitions in Dáidism

- 9 Criticism

- 10 Notes

Terminology

Adherents of Dáidism are known as "Dáide", meaning "artists", with no differentiation between the plural and singular form of the word. The word Dáidism derives from the Uryha word for the religion Dáide, rooted in the word Dáidda ('art'). Many Dáide reject the term "Dáidism", viewing the suffixing of Dáide beliefs with an "-ism" to connote a fixed and immutable worldview incongruent with the internally fluid nature of the Dáide philosophy.

Philosophy and teaching

The basis of Dáidism lies in the teachings of the ten Laalmmái. While each Laalmmái had teachings outside of those enshrined in the Laalmmái Bihcien, Laalmmái Dihkten, and the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, with several sects of Dáidism placing emphasis on other teachings, it is generally accepted that these books are the primary foundation of Dáide beliefs.

God

Dáide believe there to be a single, personal, inaccessible, omnipresent, imperishable, all-loving but not omnipotent God, both beyond human comprehension and intimately involved in the material world. It is thought that God is absolutely inaccessible from the physical realm of existence and, therefore, God's reality is completely unknowable. Dáide are therefore actively discouraged from attempting to make communion with God -- with such being seen as a fruitless endeavour -- but are required to actively acknowledge God's love for all beings in creation, and strive to use the divinity inherent within them to carry out God's morality on Earth.

God is presented in Dáide scripture without use of personal pronouns, with no reference to gender. In the Laalmmái Bihcien, it is mentioned that on many worlds God has created life, therefore God's name is always used without reference to personal pronouns, with it being viewed as disrespectful to assign worldly attributes such as language norms, understood by Dáide as arbitrary reflections of their physical surroundings, to God.

Worldly Illusion

Giellása, defined as unreality/an untruth, is one of the core deviations from the pursuit of God: where worldly vices only give the illusion of satisfaction, distracting from the process of carrying out God's morality on Earth, and sometimes hurting it.

There are three defined levels of Giellása. Mierká (mist) is the illusions created by human thought and conceptual understanding. This level involves the attachment to rigid beliefs, ideologies, and the intellectual constructs that define one's worldview. In order for a person to transcend beyond Mierká, they must let go of their ideologies and rigid frameworks and acknowledge there to be a semblance of truth within every belief structure. Dávvir (goods) is the illusions caused by worldly attachment and ego. This level includes emotional dependencies, such as attachment to personal relationships, social status, and the validation of one's self-worth through external means, and attraction to material wealth and comfort. Overcoming Dávvir requires recognition of the impermanence of these attachments and the futility of these pursuits, focusing instead on moral and spiritual values. Suoládeapmi (theft) is the attachment to any of the Three Thieves; anger, greed, and lust, which are believed to be particularly distracting and hurtful. The fate of those vulnerable to the three thieves is separation from God, and desecration of God's morality, remedied through intensive and relentless devotion.

Human identity

Dáide scripture emphasises the essential quality of every living being seeing humanity as one divine identity (Muhtan). Doctrines of racism, nationalism,[note 1] class, caste, and other such social hierarchy are thereby seen as artificial impediments to unity, and rejections of this inherent oneness; Dávvir illusions, created for the purpose of empowering a group at the detriment of another group, at odds with the inherent divinity in all things. All humans, according to Dáide scripture, have a "rational soul", providing the species with a unique capacity to recognise God's love and carry out God's morality on Earth. As a consequence of this belief in oneness, many Dáide have been involved in internationalist or world federalist groups, but, equally, many have been involved in localist groups, believing it best to foster a sense of oneness from community outward.

Service and action

The Laalmmái taught that egotism can be overcome exclusively through service with no expectation of reward (Addála). Dáide are expected to volunteer for charitable causes for at least one hour each weekend (Fállot), and regularly donate to charity, while actively encouraging others to do the same, and criticising those who would put their own self-interest ahead of the interest of everyone affected by their actions. In order to overcome egotism, Addála must be conducted in primary respect of communal interest. Addála can also take form through political advocacy; in Dáide teachings, socio-economic development is seen as the highest form of Addála that can be undertaken. Development should increase people's self-reliance, communal solidarity, and should, where appropriate, remove sources of injustice.

Justice

Dáide scripture defines justice as the state of every person's interests being fulfilled to the best ability as possible, to the point where fulfilling a person's interest would require degrading another's. According to the eighth Laalmmái, Laalmmái Jaská, "the world will be just when the last child dies a death possible to prevent". According to the ninth Laalmmái, Laalmmái Lávra, states professor of Dáide studies Dárjá Sámmol, justice should be brought about by any means, "but peaceful means of negotiation must be preferred, as to draw the sword is to turn on your fellow man; doing so means you deny their fraternal divinity, and thereby are denying your own"; if every peaceful means is exhausted, it is legitimate to "draw the sword in defence of righteousness". The pursuit of justice is seen as a duty of every Dáide, integral to living a life aligned with divine principles and to bring about the state of justice itself.

Divinity of art

In Dáidism, art is regarded as a divine expression, a medium through which the beauty and majesty of the divine can be reflected and appreciated. Artistic creation is seen as a reflection of the divine, of the pure will of a person unbound by the material world. Dáide scripture holds that the process of creating art is more significant than the final product, being viewed as the utilisation of rationality to create something greater than what was used to create it (Stuorrafiehta); with no materials being expended in order for an increase in total prosperity.

God's morality

God, according to Dáide scripture, cannot be contacted, but has a moral code which can be determined from first principles. The Laalmmái were scholars, with each of them following their predecessors' work, with their work derived from the primary truth, the Jurddat astos eallin; "thought makes life". While it is entirely possible for the outside world to be a delusion, or a dream, the only thing that can be known for sure by any person is that they exist, as without their existence, there would be no being to believe themselves to exist in the first place. Upon that, the existence of a primary creator, one responsible for the beginning of everything in existence, is assumed, and the love of this creator made evident through the self-sustaining nature of everything on the Earth and the fundamental good that is pain, and the creator's limited power is made evident through the existence of pain. Thereby, the job of humanity is to aid in the process of creation, being gifted with rationality through which they can appreciate and cultivate the world around them.

God's morality includes undying love for every corner of the world, with divinity embedded in every living thing, and humanity the most, due to human capabilities to appreciate divinity themselves. Dáide teachings thereby encourage the non-recognition of human differences such as class, caste, or nation, replaced by a universal love for all things, and a wish to ensure their prosperity. By carrying out God's morality on Earth, Dáide therefore become co-creators (Ta-dáiddarat) with God, rejecting urges to put their own self-interest first and attach themselves to the material world, and instead making the fulfillment of divine will their primary goal.

Laalmmái and authority

The term "Laalmmái" derives from the Uryha "Skuvlaalmmái", meaning teacher/educator. The traditions and philosophy of Dáidism were established by the ten Laalmmái from 1046 to 1506, with each Laalmmái adding to, reinforcing, and reinterpreting the message taught by their predecessors, resulting in the creation of the Dáide religion. Laalmmái Ertek was the first Laalmmái, and appointed a disciple of his, Laalmmái Nilá, as his successor. In the late 15th century, Laalmmái Jovnna compiled the teachings of the nine previous Laalmmái, and declared the line of succession to be over.

Laalmmái Ertek established the foundations of Dáidism with his first revelation. He wrote a book, Foundations for the Belief in God, and is said to have travelled across Entropan, teaching people the message contained within the book. Ertek stated that the Laalmmái is mortal, and so should be revered like any other mortal being, but not worshipped. Before his death, he appointed Laalmmái Nilá as his successor.

Later, an important phase in Dáidism's development came with the fourth Laalmmái, Laalmmái Joret, who began to build a cohesive community of followers with initiatives such as sanctioning distinctive ceremonies for birth and death. He established a simple system of governance for the communities, wherein a clerical leadership (Buorráneapmi) was elected directly by the communities themselves, and was the first Laalmmái to elaborate on the theory of the Worldy Illusion, building upon Laalmmái Ertek's work to advocate against attachment to worldly desire. His successor, Laalmmái Helve, founded the city of Veli, home of the Tildøs Voda.

Laalmmái Helve's successor, Laalmmái Juoksáhkká, created the Dáide Mytologiija -- a book which would later serve as the foundation for the Laalmmái Bihcien -- which contained short, allegorical stories not intended to be taken to be literally true, but rather to complement Dáide teachings. Her death, during the Siege of Veli, led to a succession crisis, due to her lack of a named successor. Laalmmái Jakub, then a member of the Buorráneapmi, proposed to directly elect the succeeding Laalmmái, which led to an ensuing election in which he won.

Laalmmái Jakub was responsible for the creation of the Tildøs Voda (Timeless throne), to serve as the supreme decision-making centre of Dáidism, allowing the Dáide religion to react as a community to changing circumstances. Representatives to the Stivra are elected by members of every Meassu, meeting only when necessary to discuss matters that affect Dáide as a whole. Laalmmái Jakub was also responsible for codifying the value of justice into Dáidism, defining it not as a value but as a goal to be strove towards.

His successor, Laalmmái Lávra, primarily concerned herself with creating art; it was with her that the divinity of art was codified into the Dáide religion, and over half of the Laalmmái Dihkten is directly attributable to herself. Laalmmái Jovnna, her successor, collated the works and teachings of previous Laalmmái into three coherent Books, and declared the line of succession to be over, and authority on the Dáide religion to be directly transferred to the Stivra.

Scripture

Dáide scripture is based off of the teachings of the ten Laalmmái, as codified in the Three Books; the Laalmmái Bihcien, the Laalmmái Dihkten, and the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, these books being curated from the written teachings of each prior Laalmmái by the final Laalmmái, Laalmmái Jovnna. While there are other teachings by each Laalmmái, followed by different Dáide sects, the Three Books are followed by almost all Dáide[note 2].

No Dáide scripture claims to have divine authority, as God is seen to be uncontactable, and therefore it would be wrong to claim God's authorship for any worldly scripture. Rather, it represents a single line of thought, developed from Laalmmái Ertek's first revelation. Dáide do not revere the scripture -- as the scripture is seen as imbued with the same divinity as everything else under God, and it openly warns against the dangers of bibliolatry -- but rather view it as a guide to moral behaviour.

Laalmmái Bihcien

The Laalmmái Bihcien (Jackian: Laalmmái Hoarfrost) compiles Muitalusaiguin (stories to be told in combination with) told by the ten Laalmmái. The Muitalusaiguin are explicitly not intended to be taken literally, but rather as allegories complementing the teachings in the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš.

Compilation and structure

The Laalmmái Bihcien started as the Dáide Mytologiija, a book of 23 mythological tales written by Laalmmái Juoksáhkká. After Juoksáhkká's death, her successor, Laalmmái Jakub, started to collect cultural myths told around Veli and compile them into historical records in the Tildøs Voda, for means of preservation. Jakub's successor, Laalmmái Lavrá, completed these volumes, writing 37 stories in the style of the Dáide Mytologiija. The Laalmmái Bihcien was the first book compiled by Laalmmái Jovnna, who also wrote in several of her own works, as well as those by various storytellers around Uryha.

Overall, the text contains 68 stories, grouped under the three Sekšuvnnaiguin (sections to be told in combination with); Eallin (life), which tells moral stories in which the ultimate message is one which recommends an action to perform, or a value to aspire to; Jápmin (death), which tells moral stories in which the ultimate message is one which recommends to avoid a certain action or value; and Ođastehkoset (renew)[note 3], which tells moral stories in which the ultimate message is one centred around the practical actions which can be taken to abide by any particular teaching.

Laalmmái Dihkten

The Laalmmái Dihkten (Jackian: Laalmmái Poems) compiles poems, hymns, and artpieces by Dáide from 1124 to 1499, particularly those of Laalmmái and other clerical figures. The intention of the Laalmmái Dihkten is to encourage artistic creation by Dáide -- as such is seen as a divine creation, as close to God as a mortal being could be; the creation of prosperity out of nothing but thought, detached from the material reality surrounding it.

Compilation and structure

The Laalmmái Dihkten began as The Compiled Works of Laalmmái Lavrá, a book published by Laalmmái Jovnna before she gained the title of Laalmmái. This book compiled several hundred artworks and poems made by Laalmmái Lavrá. Once she gained the title of Laalmmái, Jovnna began to look for other pieces of art or poems created by artists around Veli, and Uryha more broadly, which she compiled into the Laalmmái Dihkten alongside several other recovered works by previous Laalmmái, to act as inspiration to future artists and writers to contribute to the "living Dihkten"; a living compilation of Dáide art created after her death.

The text does not have a defined structure, more being a loose collection of Dáide art. According to Ernst Schau, Professor of Dáide Studies at the University of Holan, Laalmmái Jovnna believed "that the structure of the Laalmmái Dikhten should embrace a flexible, non-linear format, similar to the organic nature of divine creation itself, where order emerges not from rigid rules but from the harmonious interplay of diverse elements", with the belief that this "would encourage Dáide to view artistic creation in a similar manner".

The living Laalmmái Dihkten, the Dáide Dihkten, is a collection of Dáide art and prose from after the Laalmmái Dihkten's completion in 1506. Currently, it is housed by the archives at the Tildøs Voda, and currently contained over three million pieces of art, and over four million poems, hymns, and stories.

Laalmmái Láhkadieaš

The Laalmmái Láhkdieaš (Jackian: Laalmmái Law) compiles the primary argument of Dáidism and its consequences for morality and personal behaviour.

Compilation and structure

The Laalmmái Láhkdieaš was the first book worked on by Laalmmái Jovnna, but the last to be published. Primarily, this was due to the difficulty of obtaining reliable sources for each Laalmmái's teachings, and the often contradictory nature of these teachings, making the compilation of a coherent summary of Dáidism's primary argument challenging. The foundation for the work is Foundations for the Belief in God, a book published by Laalmmái Ertek to summarise the first revelation and the argument for the existence of God's morality.

Following this, Jovnna compiled several writings from following Laalmmái; notably, Laalmmái Nilá's expansion on the argument for God's morality, Laalmmái Jaská's writings on the value of Justice, and Laalmmái Lávra's writings on the divinity of art, as well as disparate writings by other Laalmmái. Despite the disparate nature of these writings, the Laalmmái Láhkdieaš is structured as a single train of thought, starting from the idea that Jurddat astos eallin (thought makes life), and expanding from this thought to include the primary tenets of the Dáide religion, including belief in Justice as a desirable end state, belief in the divinity of art, and belief in the fraternal divinity of all beings under God.

Other teachings

The primary argument of Dáidism evolved over the span of the ten Laalmmái, with several of the Laalmmái disagreeing on particular consequences of the first revelation, causing many works by Laalmmái to be excluded from the canonical scripture of the Dáide religion by Laalmmái Jovnna.

One of the most significant examples of a teaching excluded from the Dáide canon is the Treatise on Communal Morality and Sex by Laalmmái Jakub. It goes against the teachings recognised in Dáide canon, arguing in favour of prohibitions on extramarital sex and homosexuality, from the argument that "the divinity of all beings must be protected -- through the protection of the sanctity of the procreative process". While the Stivra of the Tildøs Voda has officially denounced this work, with the official opinion that "its logical argument falls through when it is considered that neither of the actions proposed for prohibition impact the procreative process", it has been a source of division, with, notably, the Káhttari and Álevuhta sects following the work.

The Collected Writings on the Holy is another example of a teaching excluded from the Dáide canon. Written by Laalmmái Juoksáhkká in 1314, it argued in favour of the existence of the Holy; items, people, and places that possess a level of divinity higher than other beings. It argued that the Holy can be determined from something's closeness to God: its alignment with Godly morality, becoming more divine as a result. While officially denounced by the Stivra -- due to inconsistency with the divinity of all things under God expressed by Laalmmái Ertek in description of the immediate consequences of the first revelation -- some Dáide sects still follow this text, including, notably, the Káhttari.

Observances

Observant Dáide adhere to long-standing practices and traditions to strengthen and express their faith. While the primary goal of Dáide rites is to be unobtrusive -- with the belief that the more complicated religious ceremony gets, the further it strays away from the divine -- these practices are deeply meaningful and designed to emphasise purity of intention over elaborate ritual.

Acts of worship

There are three acts of worship that are considered duties -- Rohkos (prayer), Fállot (volunteering[note 4]), and Gulahallan (communication).

Prayer

Rohkos is a daily prayer confirming recognition of the divine. It was first outlined in Laalmmái Nilá's Expansion on the Argument for God's Morality, wherein it is presented as a fundamental practice for maintaining alignment with divine principles. By reciting a short prayer, it is believed that, even if a person does not actively practice other aspects of Dáidism, they still recognise their understanding of the primary tenets of Dáidism, and thereby still have the ability to become a co-creator with God, even unknowingly. The full statement is is "I recognise the nature of the divine, and accept its presence in all beings under God. I commit to living in accordance with its guidance, and seek to align my actions with its principles". This prayer is required to be spoken every day, before midday, and Dáide are encouraged to keep a Rohkos-beaivegirji (prayer-journal) detailing the times at which they have prayed.

The daily prayer is often recited communally, in Meassu or in regular conversation between practicing Dáide.

Volunteering

Fállot is a fundamental practice in Dáidism. Every week, every Dáide is required to do at least one hour of volunteering work, with exceptions if a person is unable to carry such work out. Volunteering is considered a vital expression of faith, and one of the ways through which Dáide can become co-creators with God, manifesting the divine will by helping others without want of reward. Fállot can take several forms, primarily involving charity work and social care, with the possibility for political figures to be considered as carrying out fállot, as long as their policies and actions are socially deemed to be helping the least well-off, without desire for political or financial gain from these actions.

Large volunteer forces such as the Dáide Service Force and Dáide Relief have primary responsibility in coordinating volunteering activities, with the goal of addressing the needs of communities both within and beyond the Dáide population -- these organisations being structured to mobilise large numbers of volunteers quickly and efficiently, particularly in response to emergencies, natural disasters, and other crises.

Communication

Gulahallan refers to the practice of attending Meassu every week, to the best of one's abilities. The justification for the necessity of this practice lies in the Foundations for the Belief in God, wherein Laalmmái Ertek wrote that "Consistent communion with the community is the foundation upon which individual faith is built and sustained, and so he provision of an structured environment for reflection, learning, and the reinforcement of divine principles, should thereby be central to any who believe in the divine". No writings specify what exactly Dáide must do in Meassu, leading many to become flexible, multifaceted spaces to cater to the diverse needs of the communities surrounding them, with Dáide often opting against attending traditional service as their Gulahallan in favour of engaging in creative and intellectual pursuits.

Dáide festivals/events

While there are several festival celebrated locally in Dáide communities, there are four primary festivals in the Dáide calender.

- Bealgeloddi is the most important festival for Dáide, taking place annually on 8 January. It was initially instated in the mid-12th century as a midwinter feast to promote community cohesion, but has since become a large festival in Entropan, with customs associated varying significantly from community to community, but usually include some variant of gift-giving and a community feast typically held in a local community hub with free entrance.

- Bupmálas takes place annually during the first two weeks of April, as a celebration of art and creativity both within and outside of the Dáide community. It was instated in the late 15th century to emphasise the divinity of art and encourage more Dáide to partake in creative activities, and now it serves as a significant cultural event in Entropan.

- Vuojaš takes place annually during the last two weeks of July, as a celebration of intellectual pursuits in and outside of the Dáide community. It was established by Laalmmái Jakub in the mid-14th century to honour the importance of learning, inquiry, and the pursuit of wisdom, and now primarily takes the form of encouraging wider participation in intellectual activities and broader opportunities to enter academia, with thousands of competitions and workshops opening annually.

- Vuoktaláfol is a two-week fast that is observed annually from 1 to 14 October. It celebrates the hunger strike of the Seven Martyrs towards the beginning of the repression of the Dáide religion by the Mogyoróskan Association, with the fast principally serving as a time to reflect. The fast precludes food, drink, and smoking, until sunset, and its end is marked by the Spoađđoduoršu, a solemn, commemorative ceremony that includes readings, prayers, and the sharing of simple, symbolic meals.

Initiation

If a person wishes to undergo initiation into Dáidism, they have to read or listen to the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, in full, and then, with at least three witnesses, recite the Rohkos. This initiation was outlined by Laalmmái Jovnna in the writing Discourse on the process of initiation, published after the publication of the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, with the justification being that "The acts outlined demonstrate a person's sincere commitment to the divine, and ensure that the initiate has absorbed the teachings in full, while integrating that person into the community through a shared declaration of faith".

In the present day, initiations overwhelmingly happen informally. Informal initiation is held to more strict standards than formal initiation, with Dáide often being required to have a conversation with the initiate regarding the tenets of Dáidism, rather than accepting that they read the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš at face value. Formal initiations still exist, with most of them taking the form of readings where one person or a group of people read the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, with these initiations being mainly held by Meassu.

History

Dáidism originated around the end of the 11th century. Laalmmái Ertek (1046-1105), the founder of Dáidism, was born in the town of Mieðgaraðr, (modern-day Vuovdejávri), his parents being two pagan scholars. According to the hagiography Ahkis Laalmmái Ertek, composed five centuries after his death and primarily based upon oral tradition, Ertek was fascinated by religion as a child, often spending time with wandering ascetics and holy men, and engaging with local religious scholars and practitioners, often challenging their own views. By the age of twenty, Ertek began to develop his own philosophical ideas, influenced by his upbringing in religious spaces, but he expressed frustration with religious belief, writing in a letter to his mother "what is the fundamental basis for this religiosity, and why has it captured every person within its hold? How do we know these deities exist? How do we know the Gods exist?"

Ertek then went to a cabin on the Válidájera Mountain nearby Mieðgaraðr, where he intended to engage in deep contemplation and solitary study, particularly on the nature of knowledge, and whether anything could be known with utter certainty. For just over a week in July 1086, he set about a process of doubting every belief that he had previously held, to understand the fundamental aspect which guarantees reality; first by doubting his senses, as there is no objective difference between sensing while awake and sensing while dreaming; and then by doubting his conceptualisation of objects, as they could be deceptions by an omnipotent God who placed them there. After this, he argued, there was very little left that was assured, but eventually arrived as the statement that Jurddat astos eallin (thought makes life); known contemporarily as the first revelation. If he thinks, he reasoned, then he, on some level, must exist, because something that does not exist cannot doubt its own non-existence.

From this fundamental truth, Ertek built up a justification for the existence of God; the existence of the Self must have a cause, which in turn also has a cause, continuing until a primary, fundamental cause. As this fundamental cause cannot come from nothing, Ertek argued, as it is impossible that nothing creates something, this fundamental cause must be a conscious creator; a God. This God, Ertek argued, had to be all-loving, as an immoral being would not create life -- and thus the ability for beings to feel pleasure -- but the existence of pain suggested that this God was not all-powerful.

From the existence of this being, he built up justification for the existence of what he had previously doubted. He also arrived at the idea of an inherent Godly morality, as the capabilities for experiencing pleasure and pain are within any being, and humans know, instinctively, that pleasure is good and pain is bad, despite there being no concrete evidence towards those claims. Thereby, he argued, pleasure is the only inherent good, and pain is the only inherent evil. For a person to carry out God's morality, they must commit themselves to maximising pleasure, and minimising pain. He concluded his writing with the call for humanity to become "co-creators" (Ta-dáiddarat) with God, carrying out God's will on Earth.

Early growth (1086-1240)

After Ertek finished his contemplation, he returned to Mieðgaraðr, and bound his initial writings into a book, entitled Foundations for the Belief in God. He started to talk with some local religious authorities about the beliefs expressed in the book, where he began to formulate more a disdainful opinion of traditional religiosity as a whole, writing in his journal that "I am surprised how little argumentation was put forward against the perspective [shown in Foundations]. Unfortunately I may come to the conclusion that the vast majority of religiosity is irrational, powered by nothing but superstition and lies". The people he talked to who did reject the perspective shown in the book influenced him to edit it further, and then, eventually, he published it.

He attempted to gain support from the residents of Mieðgaraðr, proclaiming himself to be the "Laalmmái" (teacher), reading excerpts from the book and conversing about its teachings; but the village was hostile to his beliefs, and he was ultimately sentenced to exile. He then, according to most sources,[note 5] travelled around western Uryha, visiting several villages and towns to spread the message contianed in the Foundations, with the ultimate goal of creating a coherent community for what he now termed as the "Dáide religion".

Towards the end of the 11th century, Ertek's health deteriorated, and he appointed Nilá Ákkheta, a follower of his and close friend, as the succeeding Laalmmái. Laalmmái Nilá was the first to properly define how the Dáide religion should be practiced, and she expanded on the primary argument of Dáidism in her book Expansion on the Argument for God's Morality, a text which took Laalmmái Ertek's argument further, including properly arguing for the equality of all people, with the argument that all people have within them the capability to experience pleasure, therefore God exists in all. While Nilá was Laalmmái, the Dáide community grew substantially, and attracted the attention of the Uryha authorities, who viewed it as a threat to the cultural fabric of the country. As such, there were attempts at suppressing the religion by authorities, but the majority of them failed. In the middle of the 12th century, Laalmmái Nilá appointed Agát Ákkheta, her daughter, as her successor.

While Agát was the Laalmmái, followers of the Dáide religion, now primarily centred in Tjoelvege, faced considerable repression by Uryha authorities. Frequently, members of the King's Army were sent into the village to kill those who followed the religion. Not much is known about the exact extent of this repression, mostly due to it being excluded from the King's record-keeping initiatives, but it is known that the Dáide community persisted throughout, albeit being reduced in size significantly due to mass killings by the army. As tensions rose between the Kingdom of Uryha and its neighbours, however, the logistics of such an operation began to bear too much of a weight on the army, and the resources previously directed to carrying out routine checks on the village were redirected to secure major cities.

In 1195, Laalmmái Agát died, appointing Joret Ashhkána as her successor around a year prior. Laalmmái Joret expanded the Dáide community that had been growing in previous decades, placing emphasis on building a cohesive community that could unite against the forms of oppression that it had seen. He sanctioned distinctive Dáide ceremonies for birth and death, and placed an emphasis on development as a primary goal. This, he argued, would cause a "snowball" effect, making all future generations better off -- thus saving them from significant amounts of pain, aligning your actions with godly morality. Under this framework, the Dáide community expanded outward from Tjoelvege, a program supported by Laalmmái Joret despite it not being aligned with her writings. The community at Tjoelvege began to absorb much unoccupied land around its original boundaries, but with this not leading to significant development for the community, as it was, primarily, unusable land.

Later into her time as Laalmmái, Joret began to create a cohesive government for the community, declaring it as "autonomous from the central lands". With the community expanding to several thousand people, a clerical governance model was instated, based upon democratically elected clerical leadership (Buorráneapmi) who managed the domestic law of the community. In 1232, Laalmmái Joret died, bequeathing the title to Helve Jáhksákka.

While Helve was the Laalmmái, the community of Tjoelvege expanded drastically, with trade opening between itself and other cities. In 1235, the current place of the community was recognised by the clerical leadership as unsustainable for the increases in population size the community was seeing, and thereby a new settlement was founded in an existing village several kilometres southwest from the original settlement, named Veli. Veli grew quickly, taking advantage of the productive soil on the land of Veli to trade with other towns and cities and encourage population growth.

Classical era (1240-1615)

Veli remained essentially unaffected by the War of the Three Kingdoms, being far from the conflict during the war; however the vacuum opened by the Razing of Sáefi and related destruction of other towns allowed it to expand further (despite initial economic set-back), becoming a dominant power in the western Uryha region of the new Entropan, and expanding to the point where it was classified as a city by the Council of Ministers. However, this period did come with a level of tension between neighbouring cities and the community of Veli, with these tensions rising in the following decades, becoming the source of several skirmishes between opposing forces and the residents of Veli.

Laalmmái Helve died in 1281, after choosing Juoksáhkká Henddo to be her successor in the position. Laalmmái Juoksáhkká has been described by most contemporary sources as reclusive and disinterested with the prospect of governing the Dáide community, preferring to spend time writing. In 1301, she bound the Dáide Mytologiija into a book, the book being a group of allegorical stories intended to convey across other teachings by previous Laalmmái. Her absence from the responsibilities of the position of Laalmmái, and the subsequent delegation of those responsibilities to members of the Buorráneapmi, is widely considered to be the primary reason behind the worsening of relations between Veli and the Council of Ministers.

In 1325, the Council of Ministers authorised several hundred soldiers to occupy the city of Veli, ousting the council leadership and suppressing the Dáide religion as a whole. The resultant siege; the Siege of Veli; killed several thousand of the city's inhabitants, including Juoksáhkká herself, who had not, at that point, appointed a clear successor. After a successive defence against the siege, a crisis emerged where there were several competing claimants to the title of Laalmmái, and since the oral word of each successive holder of the title had been sufficient to pass the title and its responsibilities on, there were no formal mechanisms to resolve such a situation. Jakub Sámmol, then a member of the Buorráneapmi, put forward a proposition to the general assembly of the group that a direct vote of the population of the city would be held to determine the successor out of the claimants. Jakub won this election, and so became the next Laalmmái.

From 1327 onwards, Jakub began to reform the Buorráneapmi, which he believed to have become self-serving and corruptible. He replaced the system with the Stivra, a body centred in the Tildøs Voda and consistent of 63 delegates directly elected by various Meassu, who held ultimate authority in regards to organising the Dáide community, in interpretation of texts, and in rulings on the canonical texts of the scripture. While the majority of Dáide were content with this arrangement, a group of former clerical leaders defected from this, stating the body to be dangerous, undermining the purpose of the Dáide religion in pursuit of democratic consensus. From this came the modern Seibvá denomination, who still do not recognise the authority of the Stivra as established by the Laalmmái Jakub.

Later in his life, Laalmmái Jakub became more reflective, publishing On the Value of Justice, a book which codified the principle of justice into the Dáide religion as the ultimate goal that should be striven towards collectively. However, many of his other writings have been since decanonised from Dáide literature, primarily due to their socially conservative nature which conflicts with further Dáide teachings; including Treatise on Communal Morality and Sex, published in 1364 and arguing against extramarital sex and homosexuality, and On the Fundamental Inequalities, arguing for explicitly codified patriarchical institutions in the Dáide community. While, originally, these writings were codified and the structures described implemented, they were repealed by the next Laalmmái.

Before Laalmmái Jakub died in 1379, he appointed Jaská Ehétsen as his successor. Laalmmái Jaská was less publicly visible than Jakub was, spending the majority of her time in the Tildøs Voda on the political aspects of working with the Entropanian Government. Laalmmái Jaská is primarily known for her work as a stateswoman, being known as the Vuos Stáhtaolmmái (first statesperson) for her role in overseeing a dramatic increase in the production of the city, as well as for her role in de-escalating rising tensions between the city of Veli and neighbouring Evsa through a mutual trade agreement between the two cities. During her time as Laalmmái, the religion is thought to have stagnated in growth, with the city of Veli expanding to its fullest extent and attempts at spreading the religion to nearby towns and cities met with hostility and occasional bouts of violence.

Laalmmái Jaská died in 1414, with her designated successor, Laalmmái Lávra, succeeding. Laalmmái Lavrá's work forms the majority of the Laalmmái Dihkten, with over 500 poems, paintings, and songs directly attributable to her. Somewhere in the late 1390s, she began work on a defence of the inherent divinity of art, which was completed in 1403, as The Divine Rationality of the Arts and their Practice, which codified the principle of the divinity of art into the Dáide religion. She was a reclusive figure, generally preferring to give the Stivra sovereign power over her own, a break from the tradition of some previous Laalmmái. Privately, she viewed the position of Laalmmái with disdain, believing that "vesting total authority in a single person goes against the fundamental tenets of the Dáide religion", saying that doing so "makes a mockery of the divinity of all peoples".

In 1432, the death of King Oskar II led to the controversial coronation of King Fredrik -- the first Dáide king, having grown sympathetic to the teachings of the religion when he travelled to Veli a few decades prior. King Fredrik made an effort to promote the Dáide religion, including actively proselytising areas of Entropan outside the area around Veli. While this is the reason for Dáidism predominating around Entropan, King Fredrik's active attempts at suppressing other religions, including previously dominant pagan religiosities, and, for some, the nature of his power, garnered him significant criticism from Dáide thinkers at the time. Laalmmái Lavrá herself privately despised King Fredrik, calling him a "disgusting person who seems not to understand the fundamentals of the Dáide religion", writing in personal diaries that "[t]he unfortunate fact about [the policies of] the new monarch is that their foundations are upon the belief that the Dáide religion itself is supreme above all others, which just about proves that he has not read the Dáide literature, nor is he planning on doing so".

Before Laalmmái Lavrá died in 1454, she passed the title on to her daughter, Jovnna, who she had taught in accordance with her own beliefs about the title itself, with some accounts suggesting that she had explicitly told Jovnna to relinquish the title. In a speech to the Stivra in 1455, Laalmmái Jovnna made clear her intention to relinquish the title of Laalmmái upon death, ending the succession line and leaving the Stivra as the dominant body of the Dáide religion. In her view, it was clear that the existence of a title with power, beyond the influence of any person to whom such power affects, was a denial of the inherent equal divinity of all peoples.

In the early 1460s, Laalmmái Jovnna began work on the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, a book intended to document the full consequences of the primary argument of the Dáide religion -- however, she found difficulty in obtaining many of the sources for some more obscure teachings, with some archaic language in the earlier transcripts being hard to translate fully. Frustrated, she began to work instead on two other books, the Laalmmái Dihkten -- intended to document artistic endeavours by each Laalmmái -- and the Laalmmái Bihcien -- intended to document various Muitalusaiguin (stories to be told in combination with) by Dáide and non-Dáide authors, to build a Dáide mythology. In 1498, the Laalmmái Bihcien was published, with the first copy being given to the Stivra for archival purposes -- followed by the Laalmmái Dihkten in 1499 and the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš in 1503. With this, the succession line of Laalmmái was completed, and sovereign power over the Dáide religion was transferred entirely to the Stivra, at the request of Laalmmái Jovnna, in an event known as the Iehčani (sovereigntisation).

In the following decades after Laalmmái Jovnna's death in 1506, depsite initial instability, the chamber of the Stivra began to coalesce into several broad blocs. The Orthodox believed that all change in the Dáide religion should be taken in careful view of preserving the original messages and teachings of the Laalmmái, believing that such "dilution" would open the religion to damaging misinterpretations that over time would wholly corrode its foundations as a whole. Beyond the Orthodox was a group known in modern times as the Fundamentalists, led by figures such as Báhppa Eihtre and believing the works of the Laalmmái to be distinctly holy. The distinction of the Fundamentalists was their belief that the works of the Laalmmái were distinctly holy, and that any attempt at altering them was inherently wrong.

Further leftward from the Orthodox grouping of the chamber were the Transformative, a disorganised group representing the majority opinion of the Stivra for most of the 16th century. The Transformative, while respecting the works of the original Laalmmái, beleived that the Dáide religion should build on top of them, rather than expand on them -- with leaders such as Báhppa Vuolit writing on further implications of the primary argument, arguing that the Dáide religion should be a living creation, capable of responding to the needs of the Dáide community and further, as technological and scientific development was furthered. Further leftward still of the Transformative were the Constitutionalists, a small group formed in the latter half of the 16th century who held that the works of the Laalmmái were no greater than their contents, and that the entirety of the "Dáide project" was a single continuous and transformative process of discovery and philosophical debate.

Pre-modern era (17th-20th centuries)

Towards the end of the 16th century and with the spread of printing press technologies, the Constitutionalists began to spread radical literature in urban centres throughout Entropan. It is believed that Constitutionalist figures either operated out of meassu as underground organisations, or overground through the official channels of Constitutionalist-dominated meassu. Constitutionalist leaders, such as Erik Dalsen, became political figures, believing that the project of Álbapmu (democracy) in the Stivra should be applied at a national literature. Throughout the latter half of the 16th century, radical beliefs were widespread throughout urban centres, and, fearing rebellion, the Council of Ministers attempted to ban the use of the printing press outright for non-governmental operations, with new blasphemy laws citing the belief of Laalmmái Jovnna that "disorder is the enemy of progress" -- however, this ban was ineffective as policing of this law was difficult due to local resistance.

In the 1609 Stivra elections, the broad Constitutionalist group gained a majority of seats. In February 1610, a radical takeover of the Dáide religion, Casper II, the ruling monarch at the time, ordered the official dissolution of the Constitutionalist bloc in the Stivra. Once the request came to the Stivra, it was read aloud to the chamber, after which it was burnt by then-Stáhtaministtar Áppo Simit. After becoming aware of this, Casper II ordered the army to occupy the Tildøs Voda and officially "arbitrate" any proceedings in the chamber. When the army came into the chamber, Simit ordered its immediate dissolution until normal function was restored -- however, after three delegates were killed while attempting to exit, the chamber was reluctantly reconvened, allegedly under threat of execution.

This event, known as the Siege of the South Rivers, is largely regarded as what sparked the Entropanian Civil War. Once it was known that the army had occupied the Stivra, a rebellion began to forment within Veli, resulting in the formation of the New Constitutional Mass in July 1610 -- an organised Constitutionalist militia. On 8 January 1611, nearly a year since it began, the Siege of the South Rivers ended, with the New Constitutional Mass storming into the chamber and taking it from the army. The following proceedings in the chamber were under the direct influence of the New Constitutional Mass, with most Fundamentalist members of the chamber expelled due to their compliance with the army's mandate, and the chamber -- and Veli as a whole -- became, over the next few years, the base of operations for the Constitutionalists during the Civil War.

On 18 September 1615, after raiding the Great Magistrate and executing the ordinarily resident Council of Ministers, the New Constitutionalist Mass signed in a new Constitution, replacing the Kingdom of Entropan with a republican form of government, and bringing an end to the Civil War.

Republic of Entropan (1615-1801)

Many historians have characterised the new government of Entropan as a dual-authority: while the official head of government was in the National Congress, the Stivra acted as its moral centre. Each new political grouping in the National Congress was roughly affiliated with a group in the Stivra: the Liberal Party was aligned broadly to the Dáide Transformative, but primarily to the Constitutionalists who made up the vast majority of its membership, and the Democratic Convergence Party (DKP), a coalition of the former authorities of the Kingdom of Entropan, aligned broadly to traditional Orthodox and Fundamentalist groups in the Stivra who opposed the abolition of the monarchy and supported the restriction of suffrage to individuals with property.

During the early years of the Republic of Entropan, the Constitutionalists remained the dominant group in the Stivra, and thereby the Liberals remained the dominant group in the National Congress. While the Constitutionalists became more institutionally dominant in civic life, the 1696 Stivra elections saw the rise of the Káhttari group, who gained nearly an eighth of the chamber's seats. The Káhttari rejected the canonicity of the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš, Dihkten, and Bihcien, instead opting for what the group viewed as the fundamental truth behind the original works by the Laalmmái, outside of the narrative they purported that the Books spun. Seeing their elevation as a threat to the fundamental values of Dáidism due to their extremely conservative views, the Constitutionalists expelled several of their members from the chamber in 1698, on charge of undermining the democratic values of the chamber through spreading dangerous beliefs.

Over the following years, discontent rose within the Constitutionalist group, with the belief that, despite Káhttari beliefs being extreme and far removed from the sensibilities of the time, Dáide should be allowed to elect them as their representatives if they wish. What is considered in modern times as the catalyst for widespread dissent amongst the Constitutionalist group is Opposisjonesrettigheter (the Rights of Opposition), a pamphlet published in 1702 by dissenting Constitutionalist Báhppa Else that argued that as no person can be infallible, human progress is determined "by the free and unprejudiced debate of all those under God", as "all persons know of their own interests, so what is best for the group is best for all". After 10 Constitutionalist representatives in the Stivra signed the pamphlet when it was reformatted into a petition and sent to Báhppa Ára, then-Stáhtaministtar and head of the Constitutionalists, he responded in a speech to the Stivra: "it may interest some [that] the deliberate rebellion believes that those who despise our ideals and would wish to besiege our Republic should be granted warm seat in our Republic's chambers", to which, reportedly, Báhppa Else heckled "to despise the Holy man!",[note 6] to which she was expelled from the Constitutionalist group.

In 1704, following the elections of that same year, several of the Constitutionalists who signed the Rights of Opposition left the Constitutionalists in protest of their continued policy in banning fundamentalist members from the Chamber. After Báhppa Ára was murdered in 1707, the independent members rejoined the Constitutionalist group to put forward Báhppa Else to lead, with her eventually being elected unopposed in 1708 due to changing attitudes within the Constitutionalists at-large. Her first act as Stáhtaministtar was to put forward a repeal of the ban on Káhttari and other such fundamentalist groups from the Stivra, and in the premises of such pass the arguments made in the Rights of Opposition into Dáide canon.

In the 1710 Stivra elections, Káhttari and other such fundamentalist groups became the second largest theological grouping in the Chamber. Their stature rose in following elections with the aligned Party of God gaining 27 seats in the National Congress by 1738. Dissent grew from within the Constitutionalists alongside the rise of fundamentalist groups, with Báhppa István acting as an informal leader among dissenting factions.

In 1742 Báhppa István published the Commoner's Guide to Dissent and Action, a pamphlet arguing that the Stivra should represent the Constitutionalist strain of the Dáide religion, as "to argue that those who react against the current, directly against the wishes of the Laalmmái, is to argue that the Stivra itself should become nothing more than a vassal for puerile debates on the very principles the body was set up to uphold". Upon this, he argued, the Stivra should stop associating itself with groups in the National Congress, which were "representatives of the old aristocracy", and should instead become a revolutionary body dedicated to carrying out God's will directly, with a governmental function as well as a religious one. 12 of the Constitutionalists' 45 representatives signed this pamphlet, representing the largest rebellion against either of the two main groups in the Stivra in recorded history, and going on to form the Common group in the Stivra, with no official representation in the National Congress.

Over the following decades, the traditional Orthodox and Constitutionalist groups were progressively diminished in their size and influence in the chamber. The 1762 elections saw the Orthodox group reduced to just five seats, with the Fundamentalists becoming the second largest group in the chamber. The representatives of these groups were dwindling in numbers in the National Congress, with the Common's advocation of spoiling ballots causing several seats in the chamber to go unfilled. The 1780 Stivra elections and corresponding elections to the National Congress saw the Fundamentalists become the largest group in the Stivra, and second-largest group in the National Congress. Until their return to opposition in the 1783 elections, they set about canonising works that had been previously decanonised by the body. Controversial rulings on homosexuality, suffrage, and women's rights made the Fundamentalist administration of the Stivra unpopular with many, and their attempts to restrict the franchise of Stivra elections saw significant rebellion from some of their members, three of whom would defect and join the Constitutionalist group, overriding the Fundamentalists' slim majority and preventing the legislation from passing.

Second Entropanian Civil War (1798-1801)

In the 1786 Stivra elections, the Constitutionalists returned to being the largest group in the body, meaning a shift in official interpretation to a decidedly more liberal approach. 1789 saw the Common group surpass the Fundamentalists to become the second largest in the Stivra, relegating the Fundamentalists to a close third place. Many of the Decrees of the previous Fundamentalist administration were repealed by the Constitutionalists, and, following pressures in the aftermath of the 1798 elections, ended up expelling the Fundamentalists from the chamber, in an event now known to be the catalyst for the Second Entropanian Civil War.

On 17 July 1798, expelled Káhttari members led a siege on the Stivra, forcefully attempting to retake their seats in the body, but eventually failing. Due to this, Báhppa Nándor, the group's former leader, issued a declaration of independence within the city of Salomvár for a new entity, the Heavenly Kingdom of Entropan, citing "irreconcilable violations of our fundamental rights to debate as free and equal men". Many in the surrounding area of Salomvár held sympathies with the new Kingdom, and so several voluntary annexations took place of towns such as Detek, Gyurus, and Vámosoroszi.

The ruling Liberal Party, and their Constitutionalist counterparts in the Stivra, initially attempted to negotiate with the breakaway state. But, due to an aristocratic class with growing antipathy towards the Republic of Entropan as a state, primarily due to policies of land reform and progressive taxation that had incurred significant costs on their wealth, the Heavenly Kingdom of Entropan began to slowly expand, and reject proposed negotiations. Believing the Constitutionalists to be too lenient on their approach to the separatist state, the Common group led a rebellion in Sáefi, the largest city in Uryha, issuing a declaration of independence in 1800, in which they argued that the Constitutionalists had "betrayed the ideals they fought for", arguing that the "only path to peace possible is the withered blossom of war".

The instability that the foundation of the Common Association effectively dissolved the Republic of Entropan. When the Government sent army units to retake the city of Sáefi in January 1801, the army of the Heavenly Kingdom, aided by wealthy merchants within the city, launched an attack on the city of Maledonia, which succeeded due to inadequate coverage by the Republic's militia of key buildings throughout the city and popular discontent against the ruling Government. When the attack had been proven successful, the Heavenly Kingdom issued a decree that dissolved the Republic of Entropan, and officially claimed its constituent territories for the Heavenly Kingdom.

Collapse of Entropan (1801-1853)

Heavenly League

Hiláner Commonwealth

Modern era (20th century-present day)

Dáide Genocide

Main branches or denominations

Orthodox

Nelhá

Álevuhta

Seibvá

Káhttari

Other denominations

Non-denominational Dáide

Law

Prohibitions in Dáidism

The prohibitions followed by Dáide vary intensely between denominations, and are not strictly enforced, due to the belief that the outward sins (Olgid suddun: prohibitions on activities which harm other people) should take primary concern. The three primary internal sins (Sistid suddun: prohibitions on activities which harm only one person) shared near-universally are:

- Commercial gambling -- In a Decree passed by supermajority in the Tildøs Voda in July 1914, commercial gambling is prohibited for any practicing Dáide. The rationale in the Decree is that gambling institutions are "parasites" that subsist off of stealing from the working public, resulting in great pain, and great debt, towards those victimised. While the Decree prohibits all gambling, Dáide are generally not prohibited from participating in government-owned gambling facilities, such as the Postcode Lottery, and are generally taught not to scorn those who have gambled, but to offer them the support necessary to stop.

- Monasticism -- Laalmmái Agát wrote against monasticism after meeting with pagan ascetic Árenvaskkha. According to her, in the words of personal friend and scholar Albert Pásztor, mendicancy represented a "complete waste of life", saying it to be a "pitiful, self-aggrandising pursuit, completely detached from the world". Laalmmái Agát would go on to publicly write that "any ascetic, mendicant, or otherwise monastic lifestyle should be rejected by Dáide. It represents selfishness, the idea that one's own attachment to God should take precedence over the needs of the Earthly peoples". This standard has been upheld since.

- Piercings or wearing ornaments -- While a hotly contested area in modern Dáidism, piercing of the nose or ears, or wearing ornaments, is forbidden for Dáide. The justification outlined in a letter by Laalmmái Juoksáhkká was that ornaments often serve as symbols of wealth or status incompatible with the inherent equality of all divine beings, and can also lead to vanity and a focus on superficial qualities, detracting from the cultivation of the moral character of a person. In modern times, several Dáide scholars, including Áhkbevhari Veálla, have argued against this prohibition, arguing that ornamentation does not serve as symbolic of social class as it did previously, and therefore there is no harm in permitting it -- but this interpretation has yet to be codified.

There are a significant number of olgid suddun (outward sins), which harm other people. While Dáide writings often condemn particular outward sins, Laalmmái Ertek outlined in Foundations for the Belief in God the principle to apply to any consideration for what constitutes an outward sin: "If an action harms others, directly or indirectly, without resulting in a total increase in prosperity greater than the harm dealt, the action is a grave sin". The Tildøs Voda has ruled on thousands of individual actions to see whether they fit this standard.

Criticism

Criticism of Dáide beliefs have existed since its formative stages. The earliest criticism came from the established authorities in the Kingdom of Uryha, with many viewing Dáidism as a threat to the cultural identity of the country, potentially undermining established religious practices and culture due to its emphasis on simplicity and rejection of prevailing traditions. Many also believed the religion to be a meaningless game played by those who were more interested in philosophical debate than on the material world around them. During the War of the Three Kingdoms, Dáide communities were openly pacifist, leading to prominent criticism from Uryha authorities, who accused the religion of being inherently disloyal.

In recent times, many atheist and agnostic writers have criticised Dáidism for not properly opening itself up to internal critique -- while resting upon noble premises in its logical defence of God's existence, they say, the establishment of Dáidism as a religion has squandered its foundations, with -- despite attempts by Dáide authorities to encourage debate and discourse regarding the tenets of the religion -- many accepting its teachings blindly. Philosopher Junne Dure coined the term "Unquestioned rationality" to describe this in her 1913 book A modern look on the Dáide religion, where she argued that the initial intellectual rigour that underpinned the development of Dáidism has, over time, given way to a form of dogmatism, due to the inherently conservative nature of religious authority. Philosopher Rauni Lukkari, who expanded on Dure's argument of unquestioned rationality, particularly criticised the semi-deification of the ten Laalmmái, believing instead that Dáidism should be a purely intellectual tradition.

Particular criticism has been directed at the first revelation (Jurddat astos eallin: thought makes life), and the logic of the teachings derived from it. Dáide philosopher Olivér Illés published the Alternative View of Dáide Láhkadieaš -- now the basis for the Váirám denomination of Dáidism, where he rejected the premise that "thought makes life", instead basing the work upon the idea that the certainty of death makes life, and coming to different conclusions from the Laalmmái Láhkadieaš.

In modern times, the Dáide attitude towards the Entropanian colonisation of Reykanes has been extensively criticised. In her book To Fail a Life: the Dáide colonial, Entropanian theologian Helene Haugli details the history of the Stivra's compliance with Entropanian policy towards Reykanes, even when they directly conflicted with the teachings of the religion itself. According to Haugli, the action of denying Reykanes self-governance was founded on explicitly Dáide moral grounds, with politicians of the Republic of Entropan such as then-Prime Minister Georg Christensen, and high-ranking figures in the Stivra, justifying the government's actions through "appealing to a grotesque bastardisation of the Dáide ethos: one in which the Reykani needed to be "civilised" in order to become co-creators with God -- necessarily implying that in their current form, the Reykani did not share the same humanity as the "civilised" Entropanian". This attitude thereby "set the foundation for centuries of oppression", with this attitude being blamed by Haugli on the "inherent flexibility of the Dáide religion".

Notes

- ↑ Some Dáide sects do not believe nationalism to necessarily be wrong. Some view it as necessary -- in order to carry out God's morality on Earth, they argue, one must have a group identity, and morality is not strong enough to bind people together. Typically, this view is associated with Dáide fundamentalist sects.

- ↑ Only the Káhttari do not follow any of the Three Books.

- ↑ A literal translation of the name Ođastehkoset in Jackian returns "they must renew", but most Jackian translations of the Laalmmái Bihcien translate it to "renew", which has caused controversy.

- ↑ Fállot directly translates to "We all must offer", but most Jackian sources translate this as "volunteering".

- ↑ There has been contemporary dispute as to whether Ertek's voyage actually took place. His journal does not include any details about the voyage, and there are a few sources who identified him to be have stayed in Tjoelvege, several miles south of Mieðgaraðr. However, this competing interpretation is not generally accepted, as there are few accounts of him being where it is claimed he is during the voyage.

- ↑ There are differing accounts of the contents of Else's heckle -- Báhppa Ára recalled it to be "for you can tell such a thing, Holy man", and The Stivra: its Role and History, a book detailing the history of the Stivra until 1745, recalled it to be "to see you, Holy man?" -- however, the official transript of that day's proceedings wrote it to be "to despite the Holy man!", and so that is commonly agreed to be what she said.